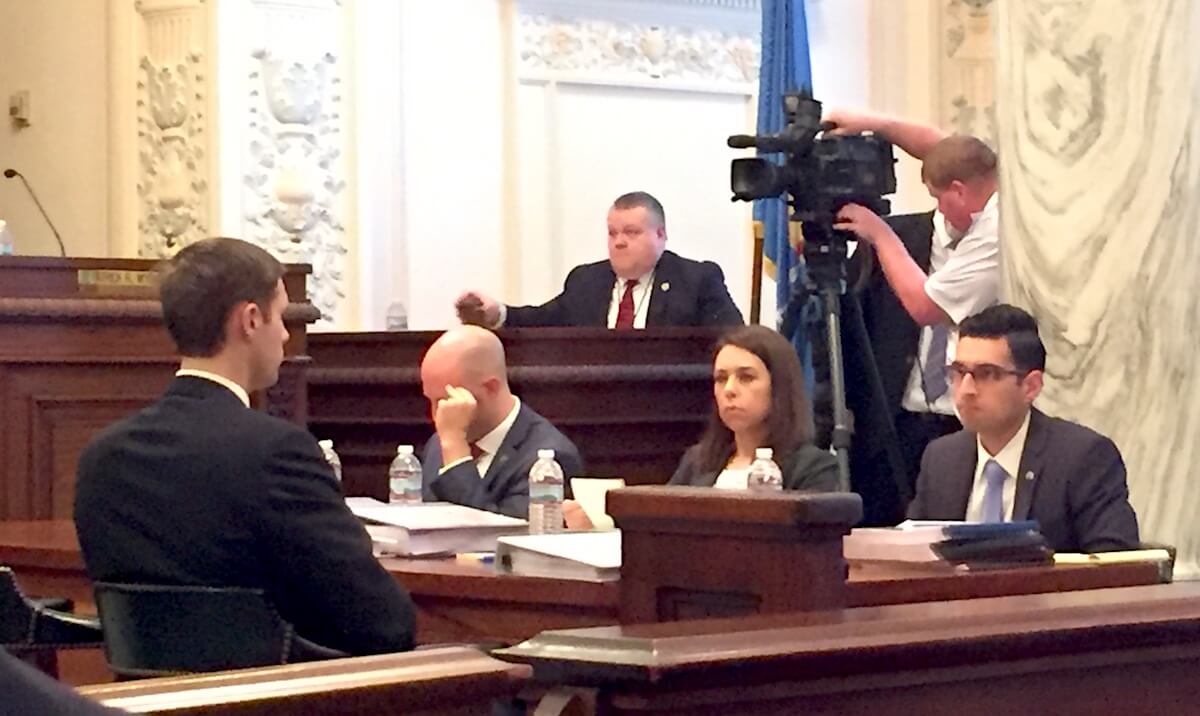

During nearly three hours of hearings this morning, Oklahoma’s newest Supreme Court justice steered much of the back-and-forth between the court and three petitioners who have challenged elements of the state’s 2017 legislative budget agreement.

“I don’t think any of us are under any illusion that the budget crisis wasn’t a key motivator. But we measure a bill by its actual effect,” Justice Patrick Wyrick told attorney Robert McCampbell during the second of three hearings.

McCampbell is representing tobacco companies who challenged the constitutionality of SB 845, which implemented a $1.50-per-pack fee on the basis that it and a handful of minor statutory tweaks would reduce smoking in the state of Oklahoma.

Lawmakers, attorneys and other onlookers have speculated over the past two months that — of the three challenges filed with the Oklahoma Supreme Court — the cigarette fee is the least likely to survive.

“The state argues for a really significant expansion of what can be considered not a revenue bill,” McCampbell told justices Tuesday.

What constitutes a “revenue raising measure” is at the heart of all three challenges. State Question 640, passed with 56 percent voter support in 1992, sets four constitutional requirements for bills raising revenue.

Norman attorney Stan Ward represented plaintiff and 2018 gubernatorial candidate Gary Richardson in the day’s third hearing. Ward was a key architect of State Question 640 more than two decades earlier, and Richardson has been a longtime political critic of the Oklahoma Legislature and Oklahoma state agencies.

He said after Tuesday’s hearings that he was surprised the court spent significant time discussing the “purpose” of the challenged bills.

“Every citizen of this state knows what the purpose was. It was to raise money,” Richardson said.

That was also the position taken by attorney Clyde Muchmore who opened the day’s hearings by representing the Oklahoma Automobile Dealers Association in their lawsuit against HB 2433. That bill removed part of the state’s sales tax exemption on the purchase of automobiles.

“This bill was passed not figuratively but literally at the 11th hour. Within five days. It was passed with a bare majority in both houses,” Muchmore said before posing the court with the question of “whether creative lawyering” can get around the SQ 640 requirements.

‘People pay more fees all the time’

All of the bills facing challenge in front of the court stemmed from GOP legislative leaders’ last-ditch effort to close an $878 million budget hole. Bipartisan negotiations at passing tax measures that require 76 House votes broke down near the end of session.

Wyrick, whose nomination and appointment to the court drew a legal challenge of its own, asked the first hearing’s second question and opened interrogation for the second. He asked several questions of plaintiff and state attorneys alike.

Concerning the repeal of the sales tax exemption on motor vehicle purchases, Wyrick asked if voters in 1992 “adopted a policy to make it harder to remove special exemptions.”

Wyrick’s line of questioning echoed arguments that GOP leaders have made publicly and privately: that any court decision saying the repeal of a tax exemption must follow SQ 640 requirements would open the door for challenges of any corporate tax incentive that has been eliminated in the past 20 years.

Muchmore argued that the motor vehicle bill’s title ought to be considered by justices, since it opens by describing itself as “an act related to revenue and taxation.”

But Justice Noma Gurich asked McCampbell and Ward how the bills they were challenging could be considered revenue bills since their titles referenced more policy-aligned concepts.

“People pay more fees all the time. The court filing fee has gone up over the years,” Gurich said to Muchmore. “Just because you pay more (it) is not a tax. I think you’re parsing words.”

Solicitor General Mithun Mansinghani represented the state in the first two hearings.

“‘Relating to revenue and taxation’ is not the test,” he said, adding that the court’s precedent drawn from the 1956 case Leveridge v. Oklahoma Tax Commission requires that a bill not only raise revenue but it also must implement a new tax. “They want you to reject your own precedent.”

Justice Yvonne Kauger expressed hesitation to accept the Legislature’s position that the bills in question were not intended as revenue-raising measures.

“It looks to me like a whole lot of parsing is going on,” Kauger said to light laughter in the courtroom. “Sort of a rose is a rose is a rose, and if it looks like a duck and walks like a duck, it’s a duck.”

‘Put it into a pile and set it on fire’

If any of the measures challenged ends up being struck down by the court, the Oklahoma Legislature could find itself pulled into a special session to address resultant budget shortfalls. The budgetary impact could simply be an across-the-board cut to agencies at a level not requiring special session. But if the cigarette fee is ruled unconstitutional, it would yield direct cuts of $70 million to the Oklahoma Health Care Authority, $75 million to the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services and $69 million to the Oklahoma Department of Human Services.

Mansinghani defended SB 845 — the Smoking Cessation Act of 2017 — by saying that increased costs for cigarettes and implemented other policy directives that would lower smoking rates and improve public health regardless of how much money the state obtained from the fee.

“The reality of the matter is, if you took all the money generated from this, put it into a pile and set it on fire, it would still save 18,000 lives because of the effects on reducing smoking,”Mansinghani said. “And that’s the principle purpose of this bill. To conclude otherwise is to conclude that 18,000 lives [does not outweigh] $225 million.”

But Wyrick called that position “extraordinary,” and McCampbell turned the hypothetical bonfire back on Mansinghani.

“It illustrates the point,” McCampbell said. “You can regulate cigarettes without creating the $225 million, which they had to have to balance the budget.”

Wyrick asked whether, by Mansinghani’s argument, a “99 percent wealth fee” could be implemented without meeting SQ 640 requirements in an effort to address income inequality.

“There’s a mountain of evidence that income inequality is bad,” Wyrick said.

The court recessed shortly before noon without offering a time frame for its decisions on the matters.

Justice Joseph Watt did not appear for any of the hearings and did not file motions recusing himself. Justice Tom Colbert recused himself for Richardson’s filing.

(Correction: This story was updated at 2:28 p.m., Tuesday, Aug. 8, to clarify what would happen if only the cigarette fee were overturned. NonDoc regrets the error.)