On April 5, Rep. Chuck Strohm used his blog to attack the Oklahoma Education Association and teachers who are currently seeking an increase in education funding. In an almost-1,900-word post, he attributed the walkout to “… the OEA [which] had to come up with a new reason for existing.”

The post from Strohm (R-Jenks), ostensibly about his dismay after a constituent asked him, “What can we pray about so that the Legislature is willing to fix the injustice [original emphasis] that has been done to our teachers?” is really a lightly informed effort to justify his obvious attempt to have his cake and eat it, too. The only “injustice” here is that Strohm gets to campaign for reelection by touting his vote for the teacher pay raise out of one side of his mouth while using the other to tout his votes against the taxes that pay for it.

‘A little knowledge is a dangerous thing’

Strohm’s post exemplifies the wise dictum, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” His views provide another example of how people with minimal knowledge of schools blame teachers and unions for complicated education problems while dictating ideology-driven solutions.

To break out of this cycle, lawmakers like Strohm must set aside their theories and come to grips with facts on the ground. Those facts are, basically, that tax cuts caused Oklahoma’s current education crisis. Meanwhile, risky, competition-driven, accountability-driven mandates within education itself have made teachers’ and students’ ordeals much worse.

Teacher salaries declined to 49th in the nation

The walkout is a grassroots uprising by exhausted educators. From fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2017, the average, inflation-adjusted Oklahoma teacher salary plummeted by $8,150. As the state’s teacher salaries declined to 49th in the nation, the average salary dropped to a level ($45,245) that is virtually identical to the average pay of 1990 — before the strike that led to the passage of the emergency clause for HB 1017.

Who sets teachers’ salaries?

Strohm tries to say that, because “actual” teacher salaries are determined by local school boards, “… if you are unhappy with your salaries, your fight should be with them.” If he were your landlord and you had no heat because he hadn’t paid the gas bill, he’d likely tell you, “It’s the gas company that turns your gas on and off. If you are unhappy, your fight should be with them.”

When it comes to teachers’ salaries, our State Constitution and the Legislature determine the revenue available to school districts. Without increased funding from property tax growth or sources controlled by the Legislature, teacher pay raises are only possible if a school districts cuts expenditures for something else. Maybe Strohm will help the Jenks Public Schools Board pay its teachers even more by using his math skills to delineate exactly from where the money is to come?

Class sizes have grown …

Strohm writes: “The problem with engineers is that we actually run the numbers rather than just believing what we are told. So, let’s do a little math.” He then calculates the student/teacher ratio to be 16.3 and concludes: “Teachers have been telling me all week that they have 28 – 30 kids per classroom, yet the NEA data says we have 16.3 kids per classroom. I would say we have a problem.”

Yes, and the problem is this legislator doesn’t understand the legislative mandates that require lower class sizes for many classes, such as special education and early childhood.

Also, the engineer doesn’t understand that 16.3 is an average, so the 28 students in the fifth-grade regular classroom are averaged with the 10 in a special education classroom. If only 12 students enroll in the high school calculus class, apparently the engineer would combine them with the 12 taking French to avoid a lower student-teacher ratio. Unlike his fantasy engineer world where every teacher and student would be interchangeable round pegs fitting into round holes and you could discard the misfits, the real world and schoolhouses of public education have a lot of square pegs.

While Strohm’s post seems to acknowledge that most teachers now have 28 to 30 students in a class, he appears to forget that secondary school teachers are likely to have 28 to 30 students in five separate classes. I doubt he has any idea about what it takes to teach 150 middle-schoolers — or how many educators have even more.

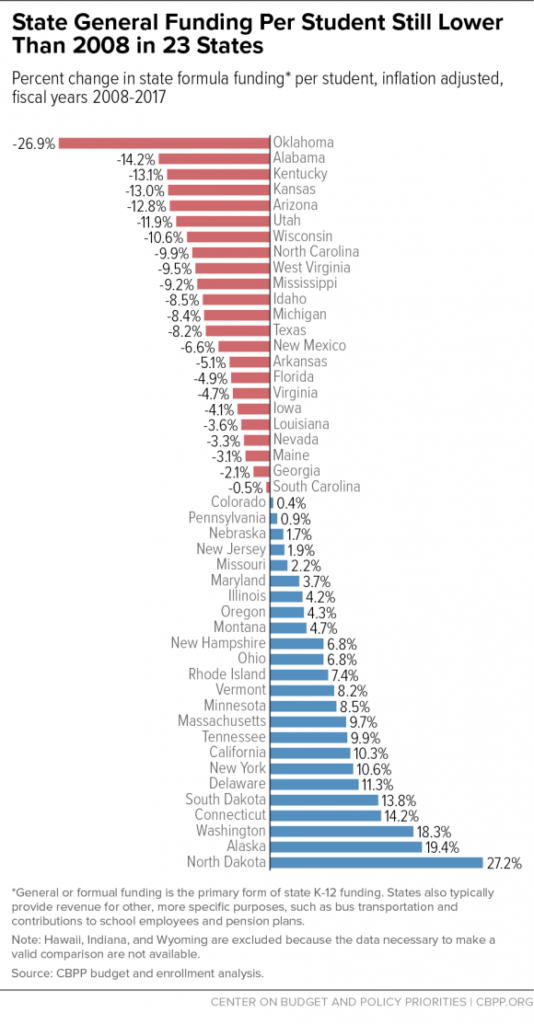

… as funding per pupil decreased

Racial and economic segregation have long been a problem, but top-down school reform increased its human costs. Competition-driven, accountability-driven reforms created more high-challenge schools with extreme concentrations of students from generational poverty who have endured multiple traumas. Those formidable challenges increase teacher attrition, creating a downward cycle for urban systems facing an acute teacher shortage. Such conditions perpetuate the myth of failing schools, full of “bad” teachers protected by “bad” unions.

In fact, Oklahoma has been spending $8,476 per student for kids in the highest poverty quintile, a whopping $6,654 per student below the cost for the state’s at-risk students to just reach outcomes at the national average. Bringing OKCPS students to the national average in outcomes would require an increase in per student spending ranging from almost 50 percent to nearly 80 percent increases for almost all OKCPS students.

There is nothing new with inner-city teachers burning themselves out, transferring to easier schools or leaving the profession, but it took a decade of fiscal irresponsibility and doomed school reforms to drive the rest of the state’s profession to that point.

Strohm half right on one thing

Strohm partly redeems himself by pointing out that the pay raise he supported (but won’t pay for) will help make our state more competitive in attracting and retaining good teachers. The Republican is also half right on one issue: “… it is about elections.”

Most teachers have long been reluctant to get involved in politics. Now, they understand that the future of their profession and their kids depend upon decisions made in the coming November. We must hope that the new commitment of teachers in terms of politics is met by a new seriousness in legislators who formulate education policy.