(Clarification: The headline on this story was modified at 12:14 p.m. Friday, Aug. 30, to better represent the change in Johnson & Johnson’s market value.)

In the 24 hours after Cleveland County District Judge Thad Balkman issued a $572.1 million ruling against Johnson & Johnson for Oklahoma to address an opioid “nuisance,” the company gained $4.9 billion in market value, Attorney General Mike Hunter declared victory and other state leaders wondered whether the Legislature had just been put in a $12 billion bind to fund a multi-decade abatement plan proposed by Hunter in court.

“Johnson & Johnson’s net earnings for the second quarter amounted to about $62 million a day,” said Rep. Forrest Bennett (D-OKC). “So we basically got approximately nine days of earnings. That tells you everything you need to know about the penalty.”

In after-hours stock trading Tuesday, Johnson & Johnson shares jumped about 5 percent (or a $13 billion value). Wednesday, the stock’s price slid back to about $129 per share, closing at a market value $4.9 billion higher than before the Oklahoma judgment was announced.

Bennett noted the stock jump as well as national attention Balkman’s verdict received, with a CNN headline opening: “Oklahoma wins.”

“Sure, on paper the judge ruled in our favor, but everything else went in the favor of the companies,” Bennett said Wednesday morning. “I’m not satisfied with this idea that the drug companies won.”

‘The order is being reviewed’

Bennett’s words might seem cynical to some, as half a billion dollars is a lot of money to any average citizen. But with Hunter, his contracted attorneys and the state commissioner of mental health seeking between $13 billion and $17 billion for 20- to 30-year abatement plans, Bennett was far from the only legislator puzzled about what comes next.

“I’m confused,” said Rep. Mark McBride (R-Moore) who attended several days of trial hearings this summer. McBride declined to speak further on the record, as did much of House Republican leadership.

“The order is being reviewed,” said Jason Sutton, communications director for House Speaker Charles McCall (R-Atoka).

Gov. Kevin Stitt’s official statement was nearly as indefinite.

“I am pleased with Judge Balkman’s decision, and I look forward to working with the attorney general and our partners in the Legislature to effectively abate the opioid epidemic across the State of Oklahoma,” Stitt said.

Senate Appropriations and Budget Chairman Roger Thompson (R-Okemah) said his Senate colleagues were also curious about the ruling’s ramifications.

“I’m still waiting on a definitive interpretation of what the judge’s ruling means,” Thompson said.

Beyond their brief statements, however, lawmakers, lawyers and other state leaders are trying to unearth solid answers to a few key questions:

- Including the Teva settlement, how much money will be available for abatement programs after attorney fees are deducted?

- How binding is Balkman’s issued abatement plan in terms of total dollars and timeframe?

- After 12 months, can the state re-attempt to prove that more than one year’s funding is necessary? If not, how much money should the Legislature designate to continue the abatement programs?

House Appropriations and Budget Chairman Kevin Wallace (R-Wellston) said he personally has not spent much time reviewing Balkman’s order because Johnson & Johnson has already announced its intent to appeal.

In a video interview with The Oklahoman’s Randy Ellis on Tuesday, a member of Hunter’s contracted counsel — Michael Burrage — said the appeals process could take two to three years. Balkman gave the state’s legal team 10 days to prepare a final judgment and offered Johnson & Johnson attorneys five days after that to make objections.

The two sides could reach a settlement to avoid the appellate process.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘Beyond year one’ lies an unknown

Wallace did speculate on the uncertainty surrounding what money would be available to the Legislature for programmatic appropriation.

“Personally, I think the net proceeds from a settlement would be the net proceeds. Attorney fees will come off of that,” Wallace said. “I have not seen a final (abatement) plan, but if there is a plan put together, I imagine it will be based on the percentages of ‘X’ amount invested in this abatement, ‘X’ amount in that abatement.”

The complexity of Wallace’s answer — and the hesitancy of legislators to speak further on the record — largely centers around the abatement plan breakdown specified by Balkman’s judgment. The district judge’s ruling did not designate money for all of the items presented in the state’s original abatement plan, which was crafted by Commissioner of Mental Health Terri White and other addiction experts.

“It is clearly a great, giant step forward in year one to build on the successes that the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services — as it states in the order — has already been leading the way on in trying to combat this problem without the necessary resources,” White said Tuesday evening. “The judgement [Monday] validated the majority of the elements presented in the abatement plan for year one, including evidence-based addiction treatment — specifically medication-assisted treatment — and the need for prevention programs, such as naloxone and SBIRT.”

But asked what strategy she and others may use to convince legislators to fund between 19 and 29 additional years of abatement programs at a cost of more than $500 million a year, White said she “can’t answer that question yet.”

“We are in the process of determining exactly what this judgment means, and I know the attorney general is working closely with the governor and legislative leadership,” White said. “As Judge Balkman made clear [Monday], he retained jurisdiction over this judgment.”

White said Tuesday evening that she had not yet spoken with any legislators or Gov. Kevin Stitt.

Asked if the attorney general could help clarify the state’s interpretation of Balkman’s abatement decision, Hunter communications director Alex Gerszewski said he could not.

“We cannot comment (…) due to the judge’s directive to the state to prepare a proposed final judgment, which by its nature addresses these issues,” Gerszewski said.

In his ruling, Balkman wrote that despite saying the crisis would take between 20 and 30 years to address, Hunter and his attorneys “did not present sufficient evidence of the amount of time and costs necessary, beyond year one, to abate the opioid crisis.”

Asked Hunter’s reaction to Balkman’s single-year abatement award, Gerszewski declined comment.

Ellis of The Oklahoman asked Hunter on Tuesday whether Oklahoma might file a challenge to the judgment amount ruled by Balkman. In response, Hunter referenced board games and a famous Will Ferrell bit from Saturday Night Live.

“Well, this is a chess game. It’s not Chinese checkers, it’s chess. So we’re thinking several moves ahead,” Hunter said. “[Burrage] has done a good job and our team has done a good job so far of getting the big picture established with regard to what the order means, what it represents. But where we go from here is, as George Bush used to say, ‘strategery.'”

Final attorney fees remain unclear

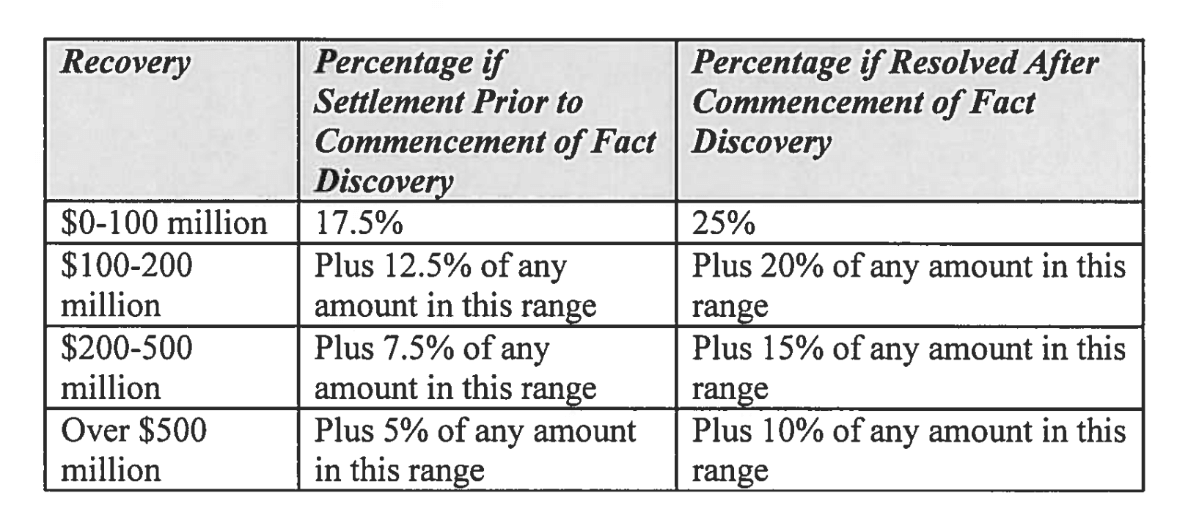

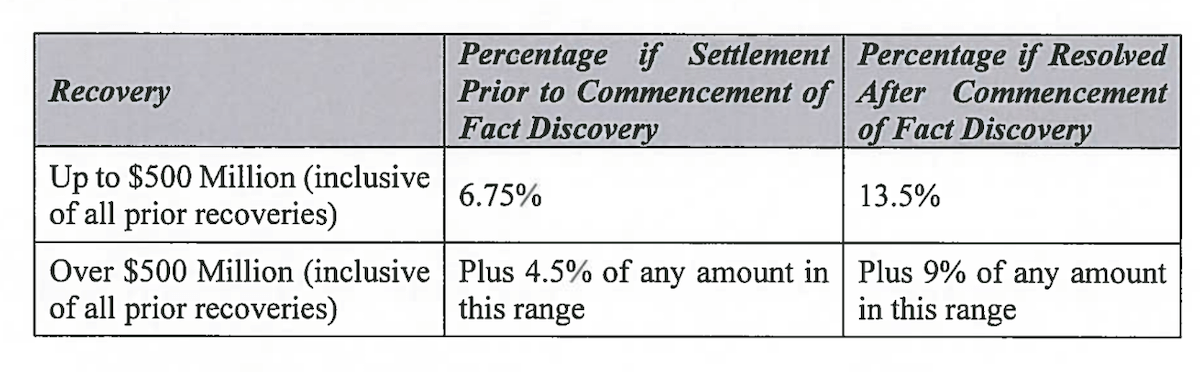

Hunter hired three private law firms to help him prosecute opioid manufacturers in 2017: OKC-based Whitten Burrage, Texas-based Nix Patterson and OKC-based Glenn Coffee & Associates. The firms originally signed the following contingency fee schedule, with resultant fees divided 57 percent for Nix Patterson, 33 percent for Whitten Burrage and 10 percent for Glenn Coffee & Associates:

In late March, Hunter announced a settlement valued at $270 million with Purdue Pharma structured in a way to support a national treatment-research institute in the Oklahoma State University system. (In May, the University of Oklahoma announced its own unrelated “national research center for addiction care.”)

On June 7 after publicizing a subsequent $85 million settlement with Teva Pharmaceuticals, Hunter and the legal firms agreed to a modification of the fee schedule for remaining defendant Johnson & Johnson. Coffee, a former leader of the Oklahoma State Senate, was removed as counsel from the revised contract, which modified the fees thusly:

Without Coffee’s involvement, Nix Patterson’s stake in the Johnson & Johnson contingency percentage became 63.34 percent while Whitten Burrage’s became 36.66 percent.

RELATED

Read the CMS letter seeking Oklahoma opioid settlement money by Tres Savage

Gerszewski said Thursday that, after attorney fees, “about $72 million” remained from the Teva settlement for abatement of the opioid nuisance. He said it would be inappropriate “to speculate on a final number with the Johnson & Johnson judgment.”

Complicating matters further for Oklahoma leaders is that the federal Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services sent a letter in June arguing that federal statute entitles CMS to a portion of the Purdue settlement.

At the time, the state had been given 90 days to respond, and Gerszewski said Hunter’s office was reviewing the situation.

Abatement: ‘Prevention, intervention and treatment’

With questions swirling about what sort of final judgement — or alternative settlement — will be presented to Balkman by Hunter and his team, it’s also unclear what will be in a final abatement plan and whether the attorney general has the ability to strike such an agreement in a way that ties the hands of the state Legislature.

Beyond that question exists another: Can elements of Oklahoma’s original abatement plan that were left out of Balkman’s ruling be added back in? (The judge’s plan begins on page 30 of his ruling, while the state’s 104-page proposal can be found here.)

“I believe everything that was included in the abatement plan is evidence-based, best-practices and gold standard in terms of prevention, intervention and treatment,” White said. “As to the specifics of the plan that are not named in the order, I look forward for discussions to understand if those components can still be included.”

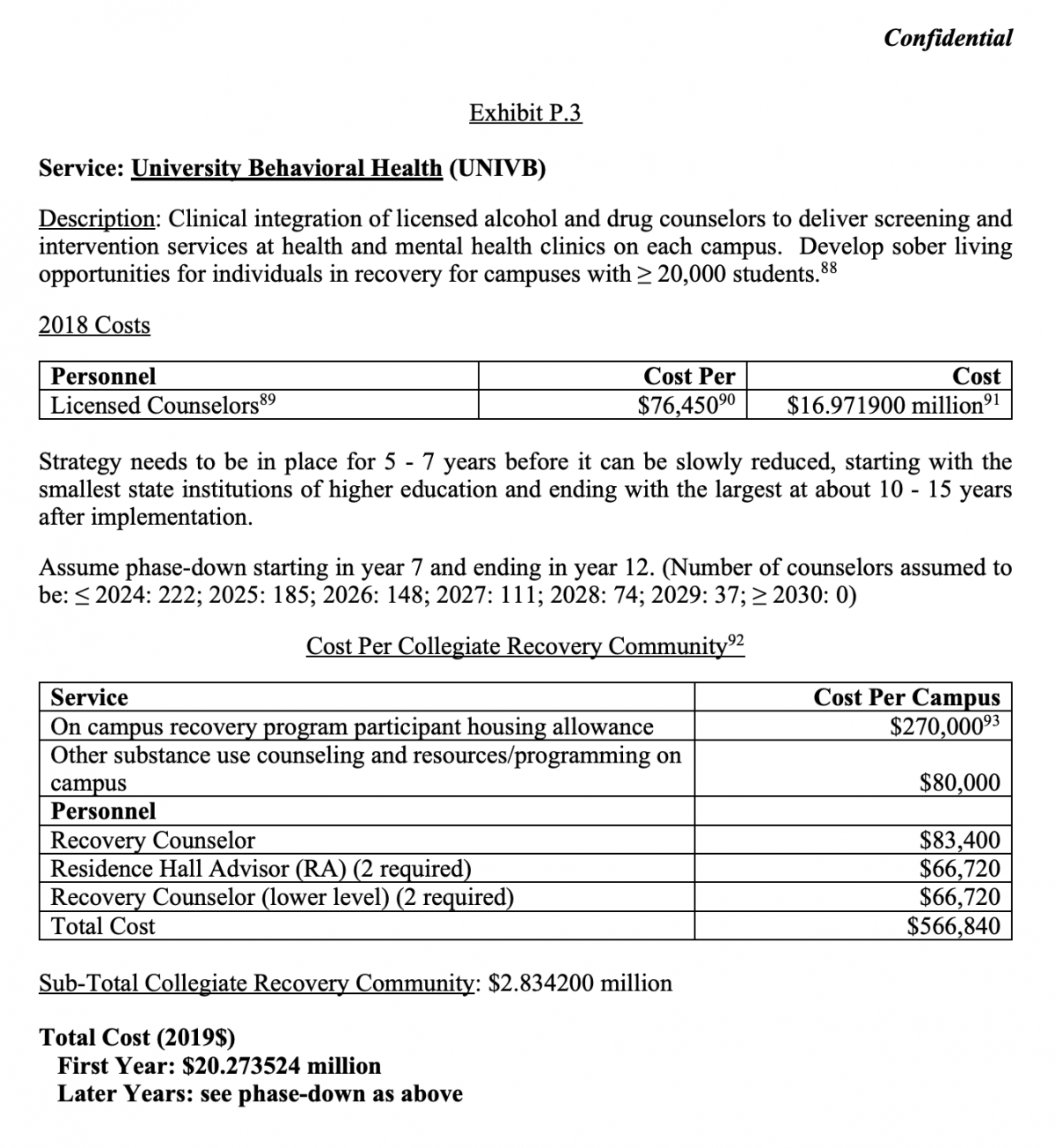

Of particular interest to some lawmakers was the state’s proposal to place 222 licensed alcohol and drug counselors (LADCs) at Oklahoma’s public colleges and universities. A potentially impactful step if guaranteed beyond one year, the proposal was estimated to cost $17 million with a “phase-down” after six years.

Balkman did not include the 222 LADC positions, but he did designate $11.1 million for training, infrastructure and an unspecified number of new state employees at medical licensure boards and other agencies.

Overall, White said Oklahoma is a national leader in terms of outcomes for people who receive substance abuse and mental health treatment.

“The dilemma that we have in Oklahoma is the door to get into services is so narrow,” she said. “We only let one out of every three people in who need help, and when two out of three people who need help can’t get help, it’s pretty difficult to recover from a disease without care.”

White said she believes the Johnson & Johnson judgment will “widen the door” for access in Oklahoma, even despite the limited abatement funding.

“I hope over the next year — the next two years, the next eight years, the next 12 years — Oklahoma continues to lead in our commitment to evidence-based practices and lead the nation in outcomes as it relates to the prevention and treatment of mental illness and addiction.”

Bennett, the south-OKC Democrat, agreed.

“I think it was the understanding and hope from everybody on the both sides of the aisle that we would have funding from these companies to tackle this not unlike TSET,” Bennett said, referencing the state’s trust created from tobacco settlement money in the mid-1990s. “I know there is a will to tackle these problems. I know there is a desire on both sides of the aisle to see positive change in these areas, but is there a will from my friends on the opposite side of the aisle to find the funding for these things (moving forward)?”

Bennett harkened back to Johnson & Johnson’s market cap climbing in the wake of Monday’s ruling, calling it “absurd.”

“This speaks to a larger problem. I don’t believe that health care should be a shareholder-centered business,” Bennett said. “It just shows that compassion takes a back seat to profit when it comes to these drug companies.”

Wallace was more coy in his criticism.

“I will say that based on the request in a lawsuit for $17 billion, $572 million sounds like a deal for Johnson & Johnson,” Wallace said.

(Editor’s note: The author of this piece is a nationally certified Mental Health First Aid instructor who is occasionally contracted by the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services to conduct trainings around the state.)