On May 13, the same day that the Oklahoma Legislature announced its annual budget agreement, the Oklahoma Department of Corrections created a “draft” proposal to close the William S. Key Correctional Center in Fort Supply, a small town in northwest Woodward County that relies heavily on the prison for jobs and economic activity.

As legislative leaders lauded their budget as a comprehensive balance of savings, tax cuts and investments that would help local communities, they knew nothing of the DOC decision to close the prison. Neither did the public until Dawnita Fogelman of the Woodward News published a June 16 article breaking the news. Fogelman had contacted DOC officials the day prior to ask about a rumor that the minimum-security facility would be closing, and on June 16 the state agency issued a press release to an unknown slate of media confirming the decision.

The news — and the way legislators learned about it — frustrated some state lawmakers, particularly those involved in the budget process and those representing northwest Oklahoma.

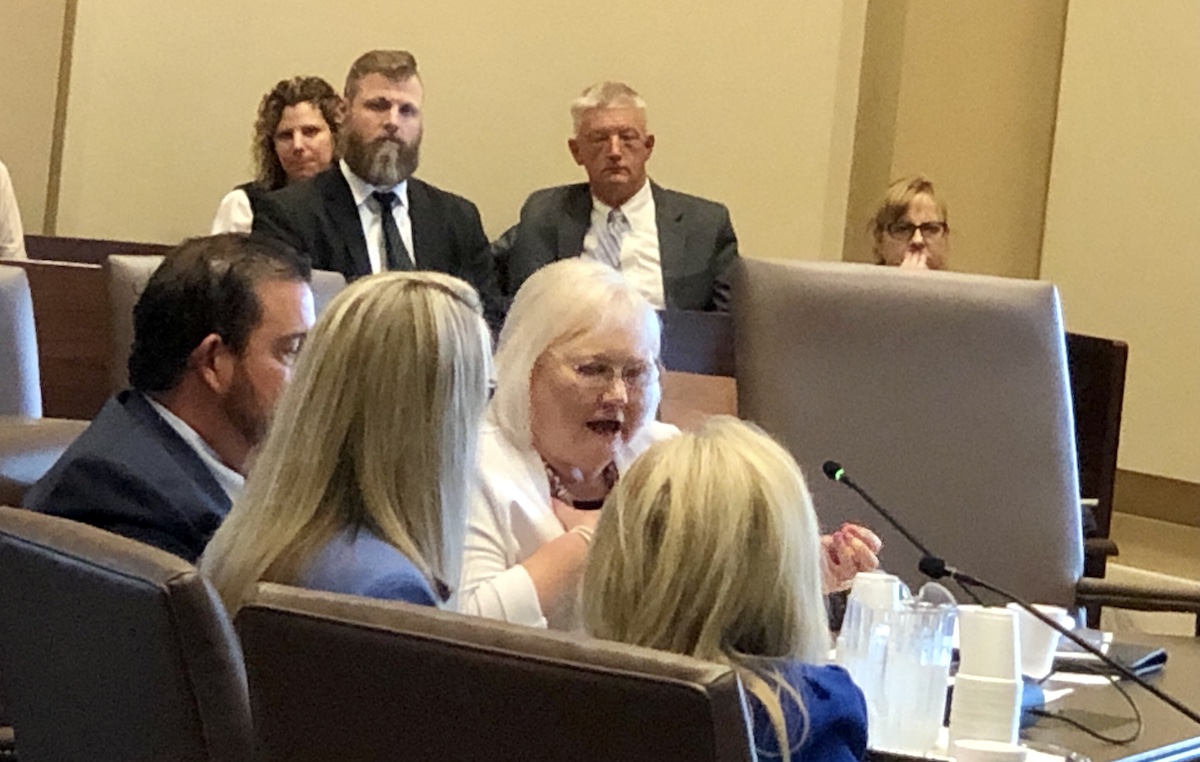

“There are winners and losers being picked, and northwest Oklahoma just seems always to come out on the losing side when it comes to investment in what we have,” said Sen. Casey Murdock (R-Felt) during a special Senate Appropriations Committee hearing today on the topic.

In opening testimony for the hearing, Oklahoma Secretary of Public Safety Tricia Everest said she only learned that DOC had announced the William S. Key Correctional Center closure after speaking with Sen. Roger Thompson (R-Okemah).

“It was certainly a hasty announcement. It was not a hasty decision,” Everest said. “With a lowering of the incarceration (rate), we don’t need the bed space.”

While emphasizing that the facility needs at least $35 million in structural repairs, Everest repeatedly referred to closing the prison by the end of 2021 as an “opportunity,” a word that boiled Murdock’s blood.

“I don’t see this as an opportunity. I see this as a death sentence to a community, (to) three different counties,” he said before asking DOC director Scott Crow a series of questions that began with how many employees work at the prison.

Crow said 142.

“Do you know what the population of Fort Supply is?” Murdock asked.

Crow replied, “I do not know that off hand.”

Murdock said the answer is roughly 350. He then asked Crow what he thinks the prison’s closure will do to Fort Supply.

“I understand, sir, that it’s a significant impact to that community,” Crow said.

Murdock then asked, “The day that you made this decision, when you went home that night. How much sleep did you lose?”

Crow responded quickly.

“Sir, I lose sleep on nearly a daily basis because of the problems in the correctional system around the state of Oklahoma,” he said. “It’s not limited to one facility or community.”

‘An important resource in history’

Beyond the enormous economic impact to Fort Supply residents and others in northwest Oklahoma, the fate of the William S. Key Correctional Center intertwines complicated state history with efforts aimed at improving the state’s future, particularly on the topic of criminal justice reform.

The prison opened in 1988 on a 3,200-acre swath of land 13 miles northwest of Woodward, and it includes the historical buildings of the original U.S. Army post that had connections to the Washita Massacre, one of the most infamous slaughters of Plains Indians in North America. Later, the fort’s mission changed to protect Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal members.

“It’s an important resource in history,” Deena Fisher, a dean emeritus from Northwestern Oklahoma State University, told lawmakers. “We had the Smithsonian out in 2018 that did an entire documentary. [If people study the] Red River wars or what happened with the massacre at the Washita, this is the site where they go to.”

Fisher, who serves as president of the Oklahoma Historical Society’s board of directors, said the facility’s historic buildings are required to be maintained by state law. She and Murdock expressed concern over who would preserve the site’s historic elements moving forward and whether funding would be available.

Since the June 16 news of the prison’s closure, Fisher said she has heard from Cheyenne tribal citizens worried about the graves of their relatives on the property. She noted that Buffalo Soldiers — a term coined by Native Americans to describe African-American Army regiments in the 1860s — were stationed there as well.

“This is huge, as far as I’m concerned. I’m sorry if I can’t do this because I am emotional,” Fisher said during testimony. “It is sacred ground, and it certainly is historic ground.”

‘That’s a huge impact’

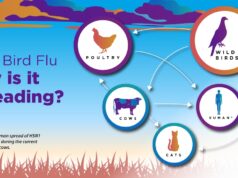

The use of historic ground as the site of a prison complex underscores the penal system problems of America, which incarcerates more people per capita than any other nation in the world. At times, Oklahoma has led the country’s per capita incarceration rate, and how best to reduce the state’s prison population has been a significant and sometimes controversial subject in recent years.

Two years ago, the state had more than 26,000 people incarcerated. But according to Crow on Tuesday, that number has dropped to 21,572. In most conversations, the state’s declining incarceration rate would be celebrated as a victory for “smart on crime” policies.

But with the 1,105-bed William S. Key Correctional Center’s impending closure, lawmakers from northwest Oklahoma and even the assistant city manager of Woodward expressed concern about the sudden decision’s economic impact on a region of the state scrambling for jobs in a precarious petroleum market.

Murdock, Woodward City Manager Shaun Barnett and others noted that talk of closing the prison has percolated before, but Fisher and Barnett said they have always had an opportunity to emphasize the historic and economic importance of the facility in the past.

“We are disappointed we did not get to voice our concerns again as a community,” Barnett told lawmakers. “[The prison is] one of the top employment facilities in northwest Oklahoma when you’re looking at the impact.”

Additional repercussions might not be as obvious to most people, he said. For instance, the prison pays about $11,000 per month to the City of Woodward for water.

“That’s a huge impact to our utility service,” he said. “So $11,000 a month is a huge impact to our community.”

Prison employees from Fort Supply — who are being offered a chance to transfer to another prison, the closest of which is 76 miles away — do most of their shopping in Woodward, Barnett said. He estimated that as a potential $500,000 impact, with another $200,000 potentially lost for private businesses that do contracting and other business with the prison.

“This is now impacting big business to small business, and as those dollars are reduced, those businesses may also have to be reducing staff as well,” he said. “We just adopted a budget with the projected revenue for the next year. We’re now having to recalculate and estimate our losses. (…) This is going to impact us for years to come.”

Barnett and Murdock also expressed concern about the effect on Harper County Community Hospital, situated about 19 miles north of Fort Supply in Buffalo.

“This is detrimental to the Buffalo Hospital. This could unintentionally shut them down,” Barnett said.

‘The facility infrastructure is deteriorating’

Thompson, the Senate Appropriations and Budget Committee chairman who led Tuesday’s hearing, said future meetings on the issue are likely.

“I’m very concerned about economical impact to the area, but more specifically to the medical impact to the area,” he said. “I remember, before my time, that when we closed the Sayre prison, we lost the hospital. I know we’re really working on health care, and I’m very much concerned about what goes on with health care.”

Thompson said the purpose of Tuesday’s meeting was to learn more about the fiscal impact of closing the William S. Key Correction Center.

“I was hoping to have gained more information about what the true savings are going to be by closing this facility,” Thompson said. “We did not hear that today. What we heard was only $1.3 million to $1.5 million on the fiscal plan. So I was a little disappointed in not getting enough information about what we’re actually saving.”

Thompson acknowledged that DOC’s decisions on what prisons it might consider closing falls under the executive branch’s jurisdiction, especially after lawmakers reorganized the Board of Corrections as more of an advisory entity.

“The Legislature does have oversight, and they need to realize we will have meetings like this holding them accountable for their decisions,” Thompson said. “I’ve asked for a meeting with the governor, and I have not had that meeting yet.”

Gov. Kevin Stitt’s communications director reaffirmed the administration’s support for closing the prison, which Stitt toured in 2019.

“As Secretary Everest said in her opening statement today, the decision to close a dilapidated and unneeded facility is the right one for our state,” said Carly Atchison. “Gov. Stitt appreciates the Department of Corrections taking steps to ensure it can best execute its mission to protect the public, employees, and the inmates and offenders, and is committed to working with stakeholders to repurpose the land to benefit the community.”

Thompson called the historical aspect of the property “major” and said he wants to learn more about how the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services will be affected. In 1908, the state’s first mental hospital was opened on the site. Eight decades later, the land and buildings in which ODMHSAS operates the Northwest Center for Behavioral Health at Fort Supply were transferred to the care of DOC, Mental Health Commissioner Carrie Slatton-Hodges told lawmakers.

She said DOC currently maintains water and sewer lines for the mental health center, which is separated from the prison by a fence. DOC also maintains the facility grounds and provides security.

“It will be at a higher price (for us to operate),” Slatton-Hodges said. “Kind of the way we found out originally as well is that we have quite a few staff whose family members or spouses who work for the Department of Corrections, so that started coming through the rumor mill.”

Everest and Crow, however, emphasized to lawmakers that the dilapidated prison needs at least $35 million in structural improvements, including an electrical upgrade, central heat and air, a new roof and foundation repairs. Each of those items is reliant upon another, Crow said.

“When we talk about $35 million, that’s not taking into account anything that is needed for foundations or walls that are leaning or walls that are separating,” Crow said. “There are a whole lot of variables that play into this, but the most serious is that the facility infrastructure is deteriorating, and it has deteriorated over a number of years.”

The day’s testimony, however, did not curb the concerns of Murdock, who peppered DOC officials with questions, soliloquies and sarcasm. At times, his hands shook and voice quivered in a line between frustration and palpable anger.

“The travesty that has happened in Fort Supply has been ongoing for years,” he said. “Why did it get to this point? Because where the money goes and the budget goes to fix these is to upper management.”

Everest and Crow emphasized that neither was in their current position when past administrators decided how to spend the $160 million in correctional facility bond money authorized by the Legislature during Gov. Mary Fallin’s administration. None of the money was dedicated to the William S. Key prison.

“We cannot justify the continued expenditure of tens of millions of dollars of state funds to patch up a state facility that is no longer needed,” Everest said.

Murdock said it’s hard for his constituents — who packed the Senate conference room Tuesday — to hear such a statement.

“With the downfall of the oil community, northwest Oklahoma is desperate for jobs,” he said. “The ripple effect in the economy up there is going to be dramatic. More than likely we are going to lose a hospital over this.”

(Update: Fewer than 10 minutes after this article published, it was updated at 5:50 p.m. Tuesday, June 29, to include a quote from Atchison.)