In a 5-1 decision from the Oklahoma Supreme Court filed Monday, justices reversed the $465 million verdict against Johnson & Johnson in the state’s high-profile 2019 opioid trial. The court’s majority opinion held that Cleveland County District Court Judge Thad Balkman “erred in finding J&J’s conduct created a public nuisance” and went “too far” in his order “creating and funding government programs designed to address social and health issues.”

“The state’s allegations in this case do not fit within Oklahoma nuisance statutes as construed by this court. The court applies the nuisance statutes to unlawful conduct that annoys, injures, or endangers the comfort, repose, health, or safety of others,” Justice James Winchester wrote in the majority opinion. “But that conduct has been criminal or property-based conflict. Applying the nuisance statutes to lawful products as the state requests would create unlimited and unprincipled liability for product manufacturers; this is why our court has never applied public nuisance law to the manufacturing, marketing, and selling of lawful products.”

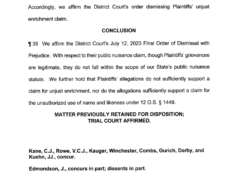

Joining Winchester in the ruling were Chief Justice Richard Darby, Vice Chief Justice John Kane IV, Justice Noma Gurich and Justice Dana Kuehn.

Kuehn authored a concurring opinion “to discuss why Oklahoma nuisance law is not, and unless the Legislature amends it, never will be, a tort.”

“Oklahoma public nuisance law involves injury to public property and a private person’s lack of capacity to correct that harm,” Kuehn wrote. “The state of Oklahoma sues to abate the wrong and ensure the elimination of the public nuisance. A public nuisance is a criminal misdemeanor with a penalty under [Title 21, Section 1191]. Understanding the plain language of the public nuisance statute, the majority finds that marketing a product is not within that definition. I am concerned that, because some believe the statutory language is vague, it leads to any interpretation of what a public nuisance can be, including marketing a product. The Legislature should consider re-examining the public nuisance statute to prevent further misapplications.”

Justice James Edmondson was the lone dissenter on the court, but even he wrote that he also disagreed with the District Court’s judgment.

“The judgment of the District Court should be reversed and the matter remanded for a correct determination of a public nuisance and damages,” Edmondson wrote. “The District Court’s findings of fact are sufficient to show the attorney general possessed a cause of action for a public nuisance common-law action. However, the District Court’s findings include matters extraneous to the trial defendants’ conduct in Oklahoma, and the findings refer to manufacturing and marketing opioids in the United States by the defendants. The public nuisance cause of action in this case must be limited to wrongful conduct by the specific trial defendants when marketing their opioid products in Oklahoma.”

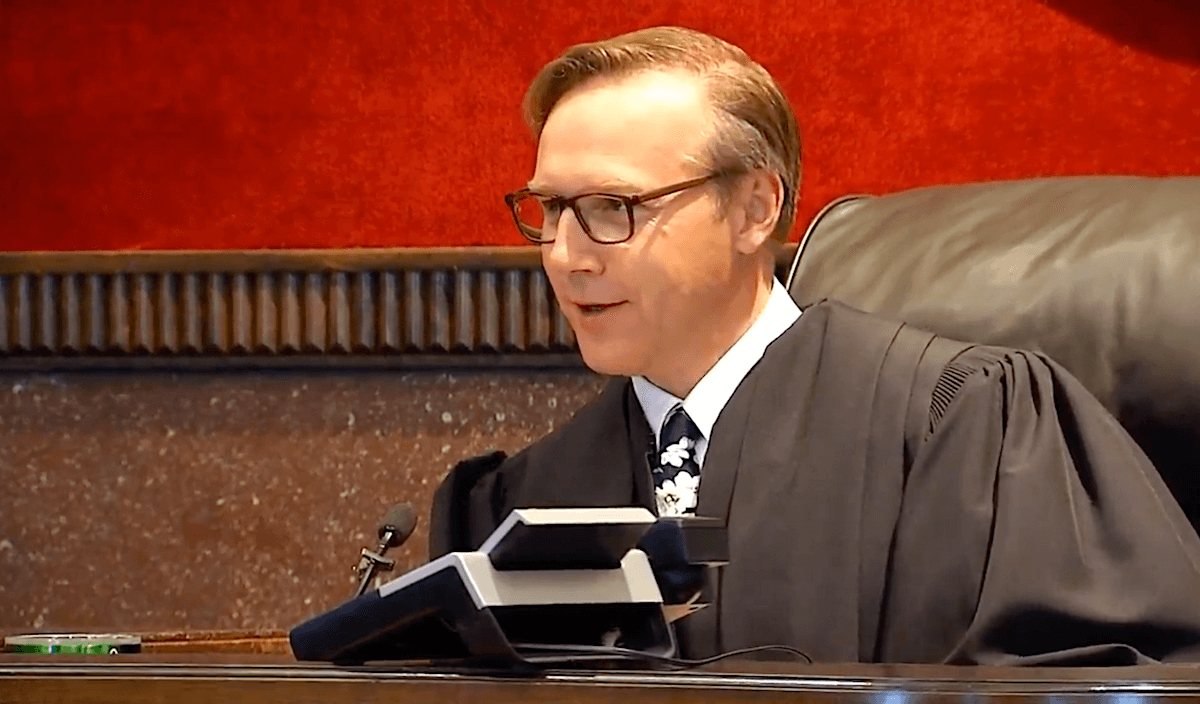

Balkman told NonDoc this morning that he would not be commenting on the Supreme Court’s decision, from which Justice Dustin Rowe recused and Justices Yvonne Kauger and Douglas Combs were disqualified.

Background on Oklahoma’s opioid lawsuit

Months after Mike Hunter was appointed attorney general by then-Gov. Mary Fallin, he stood alongside influential private attorney Mike Burrage at a June 2017 press conference to announce that the state of Oklahoma was suing more than a dozen pharmaceutical companies for allegedly misleading and pernicious marketing of prescription opioids.

“This lawsuit is about money that the taxpayers have been out because of the treatment, but it’s also about much more,” said Burrage, whose law partner, Reggie Whitten, has been one of Oklahoma’s leading advocates for addiction awareness and treatment. “The practices these pharmaceutical companies have engaged in, the lives that have been destroyed because of their fraudulent actions, have to be stopped.”

Hunter described Whitten and Burrage as “the A-team,” and they quickly contracted with the powerful Texas law firm Nix Patterson to pursue the state’s case.

Over the subsequent 24 months, Hunter announced a controversial settlement with Purdue Pharma, a separate settlement with Teva Pharmaceuticals and went to trial against Johnson & Johnson and its subsidiaries. The parties agreed to a bench trial where Balkman, and not a jury, would decide the matter. National media camped out in Norman, and the trial was streamed live online in partnership with The Oklahoman. (Hunter had appointed The Oklahoman’s editor as one of three people to oversee $177.5 million of the settlement with Purdue Pharma, which Hunter unilaterally dedicated to support a newly created addiction research facility called the Oklahoma State Center for Wellness and Recovery in Tulsa.)

Ahead the Johnson & Johnson trial, Hunter and his team dismissed their more traditional tort claims and focused solely on the public nuisance allegation, a decision that some observing trial attorneys worried was risky.

Whitten declined to comment on the Supreme Court decision Tuesday.

Balkman presided over the landmark case in the summer of 2019, eventually determining that Johnson & Johnson had created a public nuisance with misleading and harmful marketing practices that encouraged physicians to distribute opioids at a rate that led to widespread addiction to the drugs.

Balkman awarded the state $465 million for one year of nuisance abatement efforts, instead of the 20 to 30 years that Hunter, his contracted private law firms and then-Commissioner of Mental Health Terri White had requested. (The abatement plan involved funding treatment and education efforts, as well as hiring new employees at a variety of health-related state agencies, boards and commissions.)

Neither Hunter and his team nor Johnson & Johnson’s attorneys were happy with the verdict. The multinational pharmaceutical corporation argued that the public nuisance designation had been inappropriately applied, and Hunter said Balkman erred in funding only one year of the state’s proposed abatement plan.

The appeal sat before the Oklahoma Supreme Court for nearly two years, and in May of this year Hunter tendered his resignation as attorney general, leaving office before his signature case had concluded.

While Nix Patterson was named “The 2019 Trial Team of the Year” by the National Trial Lawyers organization for winning the case in Cleveland County District Court, other attorneys and their clients have been frustrated by the lack of money actually reaching communities affected by opioid addiction.

“Mike Hunter and now (Attorney General) John O’Connor have been obstructive and not helpful in getting funds to Oklahoma cities and counties to abate the opioid problem,” said Alex Yaffe, whose law firm represents nearly 80 cities, counties and sovereign tribal nations. “There has been zero money allocated to local governments through the legislation that was passed.”

Yaffe pointed to the cancelled Oct. 29 meeting of the state’s Opioid Abatement Board, which lawmakers created to distribute the roughly $25 million designated for cities and counties in the state’s other pharmaceutical company settlements.

“It’s a quagmire,” Yaffe said.

O’Connor released a statement on the Johnson & Johnson opioid decision Tuesday afternoon.

“The judgment holding Johnson & Johnson accountable for their deceptive actions was a huge victory for Oklahoma citizens and their families who have been ravaged by opioids,” O’Connor said. “I am disappointed in the decision. Our staff will be exploring options. We are still pursuing our other pending claims against opioid distributors who have flooded our communities with these highly addictive drugs for decades. Oklahomans deserve nothing less.”

Johnson & Johnson representatives also released a statement.

“We recognize the opioid crisis is a tremendously complex public health issue, and we have deep sympathy for everyone affected,” the Johnson & Johnson statement read. “The company’s actions relating to the marketing and promotion of these important prescription pain medications were appropriate and responsible. Today the Oklahoma State Supreme Court appropriately and categorically rejected the misguided and unprecedented expansion of the public nuisance law as a means to regulate the manufacture, marketing and sale of products, including the company’s prescription opioid medications.”

Details on state settlements with other pharmaceutical companies

Hunter had announced his $270 million settlement with Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, in March 2019.

The settlement required $102.5 million to be paid by Purdue and $75 million over a five-year period by the families of Dr. Mortimer and Dr. Raymond Sackler, two of the three deceased brothers who bought Purdue as a small company in 1952. Purdue was required to provide an additional $20 million in addiction-related treatment medications — think methadone or suboxone — $59.5 million to the outside attorneys assisting Hunter and $12.5 million to be disbursed to Oklahoma counties and municipalities.

A wave of litigation from across the country was filed against Purdue around the time of Oklahoma’s suit, but the state was the first to get a court date. The decision to settle with Purdue before the matter went to trial came as other states and jurisdictions were joining together in their suits against Purdue, and Oklahoma’s settlement drew criticism from some victims and advocates who wanted to see the company held accountable in court.

Hunter was also criticized — and accused of violating the law and his constitutional responsibilities — by Gov. Kevin Stitt and legislative leaders for writing into the settlement that $177.5 of the Purdue money would be sent to a new center for addiction treatment at the Oklahoma State University’s Tulsa health complex. Hunter’s son had been hired by the OSU Center for Health Sciences a few months before the settlement, which he called a coincidence.

In September of this year, Purdue reached a settlement in bankruptcy court that required dissolving the company and using its assets largely to fund efforts to combat the opioid epidemic. The national settlement was also criticized for largely shielding the Sackler family, who received an estimated $10 billion from opioid sales and were required to pay $4.5 billion as part of the settlement.

In June 2019, Oklahoma finalized a settlement with the Israeli company Teva Pharmaceuticals for a total of $85 million.

The settlement also stipulated the following:

- Teva Pharmaceuticals will not engage in or employ any third party to engage in the promotion of opioids in Oklahoma until Dec. 31, 2026;

- Teva Pharmaceuticals will provide “reasonable assistance” to law enforcement investigations of potential diversion and/or suspicious circumstances involving opioids in Oklahoma;

- Teva Pharmaceuticals may continue to sell opioids in the state of Oklahoma.

The settlement amount — minus $12.75 million in attorney fees — was directed to the state treasury owing to legislation passed following the Purdue settlement requiring that settlement money be allocated by the Legislature.

Read the majority opinion in the Supreme Court’s opioid ruling

In his majority opinion (embedded below), Winchester repeatedly emphasized that the public nuisance standard was misapplied.

“This case challenges us to rethink traditional notions of liability and causation. Tort law is ever-changing; it reflects the complexity and vitality of daily life,” Winchester concluded. “The state presented us with a novel theory — public nuisance liability for the marketing and selling of a legal product, based upon the acts not of one manufacturer, but an industry. However, we are unconvinced that such actions amount to a public nuisance under Oklahoma law.”

Earlier in his opinion, Winchester said the Legislature and the state’s executive branch were the appropriate bodies to develop abatement plans for Oklahoma’s opioid addiction problem:

The court has allowed public nuisance claims to address discrete, localized problems, not policy problems. Erasing the traditional limits on nuisance liability leaves Oklahoma’s nuisance statute impermissibly vague. The district court’s expansion of public nuisance law allows courts to manage public policy matters that should be dealt with by the legislative and executive branches; the branches that are more capable than courts to balance the competing interests at play in societal problems. Further, the district court stepping into the shoes of the Legislature by creating and funding government programs designed to address social and health issues goes too far. This court defers the policy-making to the legislative and executive branches and rejects the unprecedented expansion of public nuisance law. The district court erred in finding [Johnson & Johnson’s] conduct created a public nuisance.

Loading...

Loading...

(Update: This article was updated at 2:10 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 9, to include statements from O’Connor and Johnson & Johnson. It was updated again at 9:05 p.m. to correct a timeline element.)