In a victory for Gov. Kevin Stitt’s legal effort to limit the effects of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, a 5–4 decision released by the court this morning in the case Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta found that the state holds concurrent jurisdiction with tribal nations and the federal government to prosecute crimes committed by non-Indians against Indians on reservation land.

Attorney General John O’Connor, who will have six months of a lame-duck term remaining after he lost Tuesday’s Republican primary, heralded the victory in a press release.

“This decision significantly limits the impact of McGirt,” O’Connor wrote. “It vindicates my office’s years-long effort to protect all Oklahomans — Indians and non-Indians alike — from the lawlessness produced by the McGirt decision. While we still have a long road ahead of us to fix all of the harms our state has experienced as a consequence of McGirt, this is an important first step in restoring law and order in our great state.”

A statement by Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. was harshly critical of the decision, saying the U.S. Supreme Court “ruled against legal precedent and the basic principles of congressional authority and Indian law.”

“As we enter a chapter of concurrent jurisdiction, tribes will continue to seek partnership and collaboration with state authorities while expanding our own justice systems,” Hoskin wrote. “We hope that with these legal questions behind us, Gov. Stitt will finally lay his anti-tribal agenda to rest and come to the table to move forward with us — for the sake of Oklahomans and public safety.”

A statement from Muscogee Nation press secretary Jason Salsman called the decision “an alarming step backward for justice on our reservation,” saying it “hands jurisdictional responsibility in these cases to the state, which during its long, pre-McGirt, history of illegal jurisdiction on our reservation, routinely failed to deliver justice for Native victims.”

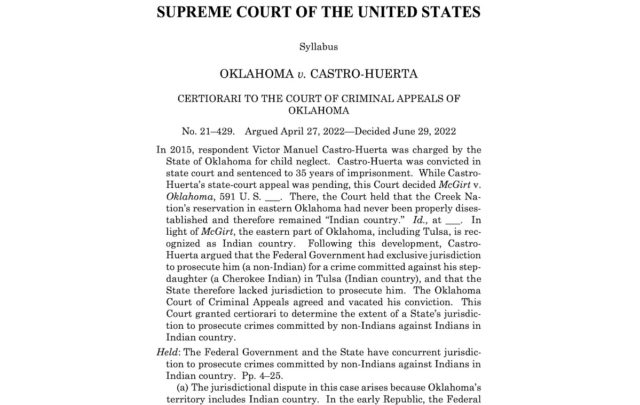

In its petitions, the state had originally asked the court to consider overturning the McGirt decision entirely, which the justices declined to do. Instead, justices considered whether, under the McGirt ruling that functionally affirmed eastern Oklahoma as featuring six Indian Country reservations, the state of Oklahoma had the authority to prosecute Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-tribal citizen who was convicted in 2015 of child neglect committed against his step-daughter, a Cherokee citizen.

After the McGirt decision led to eastern Oklahoma, including the area where the crime was committed, being under only tribal and federal jurisdiction for the prosecution of major crimes, Castro-Huerta’s state conviction was vacated and he was re-convicted in federal court.

Details of the Castro-Huerta decision

Like the McGirt decision, the Castro-Huerta case was decided roughly along liberal-conservative lines, with the exception of Trump appointee Justice Neil Gorsuch, who was by joined the court’s more liberal justices in the majority opinion for McGirt and in the dissent for Castro-Huerta. The replacement of Ruth Bader Ginsberg by Amy Coney Barrett shifted the weight of the majority.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion in the Castro-Huerta decision, which focused on two main areas: law-enforcement challenges raised by McGirt and various legal precedents regarding potentially overlapping jurisdictions.

The opinion cites the state’s estimate that 18,000 cases per year will have to be handled by a federal system not previously equipped to manage such a large number, and it refers to a “a now-familiar pattern” of convicted criminals being given lighter sentences.

These facts, the opinion says, raise the “sudden significance of this jurisdictional question for public safety and the criminal justice system in Oklahoma.”

The opinion also refers to “inherent state prosecutorial authority in Indian Country” and concludes that “the court’s precedents establish that Indian Country is part of a state’s territory and that, unless preempted, states have jurisdiction over crimes committed in Indian Country.”

To deny the state authority to prosecute crimes against tribal citizens and leave such cases to federal and tribal authorities would be to “treat Indian victims as second-class citizens,” the opinion argues.

In a scathing dissent, Gorsuch, who wrote the majority opinion in McGirt, calls the Castro-Huerta decision “embarrassing” and a “pastiche of a legislative process” and says “a more ahistorical and mistaken statement of Indian law would be hard to fathom.”

Gorsuch argues that the majority position cherry-picks certain precedents without regard to context and ignores “a mountain of statutes and precedents making plain that Oklahoma possesses no authority to prosecute crimes against tribal members on tribal reservations until it amends its laws and wins tribal consent.”

Gorsuch argues that there are established, legislative methods for the state to pursue concurrent jurisdiction on Indian land, which other states have employed, and he criticizes the state for using the courts instead.

“The state could have employed the procedures of Public Law 280 to amend its own laws and obtain tribal consent,” Gorsuch writes. “Instead, Oklahoma responded with a media and litigation campaign seeking to portray reservations within its state — where federal and tribal authorities may prosecute crimes by and against tribal members and Oklahoma can pursue cases involving only non-Indians — as lawless dystopias.”

In a recent interview with NonDoc, Gov. Kevin Stitt said he believes it is his duty as governor to limit the effects of McGirt, both in the area of criminal jurisdiction, as raised by Castro-Huerta, and in potential challenges to the state’s authority to control taxation and regulation on tribal lands.

The administration’s reaction to McGirt has exacerbated a strain in state-tribal relationships, but Stitt said preserving the state’s authority must take precedent over maintaining friendly relations.

“You would always love to have great relationships with with everyone,” he said. “But the state’s gonna move forward regardless. I mean, they’re a special interest group and of course I don’t begrudge them for fighting.”