A U.S. District Court decision in a case concerning a city of Tulsa traffic violation that involved a member of the Choctaw Nation was reversed Wednesday by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. The case now heads back to federal district court where it will likely garner additional attention as the state of Oklahoma and sovereign tribal nations continue to litigate jurisdictional disputes following a 2020 landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision.

The reversal in Hooper v. City of Tulsa came after the 10th Circuit ruled Section 14 of the Curtis Act, a law predating Oklahoma statehood, no longer applies or grants jurisdiction to Tulsa to enforce city rules and regulations.

Signed into law by President William McKinley in 1898, the Curtis Act amended the Dawes Act in an effort to break up tribal governments and communal lands in Indian Territory. Section 14 of the Curtis Act allowed for municipalities to be established within Indian Territory under certain conditions and empowered them to enforce laws and ordinances within municipal limits.

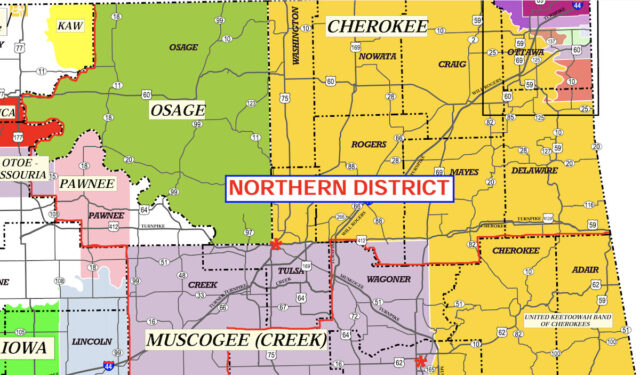

In 2018, Justin Hooper received a $150 speeding ticket within Tulsa’s city limits and the boundaries of the Muscogee Reservation, which the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed is still in existence with its July 2020 ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma. Five months after the McGirt decision, Hooper filed an application for post-conviction relief with Tulsa Municipal Court.

Since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Congress had never disestablished the Muscogee Reservation, Hooper argued Tulsa lacked jurisdiction to prosecute him, a Choctaw man in Indian Country, for violation of a municipal ordinance. In U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma, Judge William P. Johnson granted the city’s motion to dismiss Hooper’s case.

Hooper appealed, and on Wednesday the 10th Circuit ruled that although the city of Tulsa was incorporated in 1898, prior to the Curtis Act, Tulsa developed a city charter and reincorporated when Oklahoma became a state in 1907, effectively relinquishing any jurisdiction granted by the Curtis Act. The appellate court remanded the case back to the district court for “proceedings consistent with this opinion.”

In Tulsa’s appellate court brief, the city warned that reversing the district court’s decision would lead to a “system where municipal laws would only apply to some inhabitants, but not others, depending on a complex algorithm with variables based on tribal membership of a defendant as well as discrete geographies within the city limits.” The state of Oklahoma filed an amicus brief in support of the city.

John M. Dunn, the attorney for Hooper, argued in his brief that the McGirt decision means Oklahoma municipalities located within Indian Country reservations have no right to prosecute crimes committed by tribal citizens.

“The district court failed to recognize that reservation status has a broader impact. Crimes not described in the [Major Crimes Act] committed by Indians in Indian Country are subject to either federal or tribal jurisdiction under federal law,” Hooper wrote. “Like the state, Tulsa’s municipal judicial authority on the Muscogee (Creek) and Cherokee Reservations is limited to authority to prosecute crimes by non-Indians against non-Indians.”

Most of the sovereign tribal nations whose reservations have been affirmed within Oklahoma boundaries filed amici briefs in support of Hooper’s case. While the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Quapaw and Seminole nations filed a joint amicus brief, the Muscogee Nation filed its own amicus brief.

“The nation presently exercises highly effective criminal law enforcement throughout its reservation — including in traffic matters — in close cooperation with other governments,” wrote Geri Wisner, attorney general for the Muscogee Nation. “Reversing the district court’s decision will allow that cooperative enforcement to continue to flourish, while affirmance will lead to a range of unwelcome consequences.”

In writing her decision, however, 10th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Carolyn McHugh focused more on a need for Hooper and the City of Tulsa to follow a different court process for adjudication than on the ultimate question of whether the city can write a traffic ticket against a tribal citizen. Specifically, McHugh emphasized the Curtis Act being an inapplicable reason for dismissal by the district court.

“Both Tulsa and Mr. Hooper speculate about possible unintended consequences of either affirming or reversing the district court, but ultimately, we are limited to interpreting the law Congress enacted and not the parties’ ‘dire warnings,'” McHugh wrote. “Accordingly, even if Tulsa proves correct that reversing the district court’s decision will lead to disruption, we must base our decision on the plain text of Section 14 (of the Curtis Act). If the system in place in Oklahoma proves untenable, ‘Congress remains free to supplement its statutory directions about the lands in question at any time.'”

Stitt fears ‘no rule of law,’ Hill says ‘sky is not falling’

Michelle Brooks, Tulsa’s communications director, said late Wednesday that the city’s legal department is reviewing the opinion and will be evaluating next steps.

But on Friday, Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum announced on social media that he was authorizing the city’s attorneys to request that the U.S. Supreme Court hear an appeal to the 10th Circuit’s decision.

“When the Supreme Court issued their ruling (in McGirt v. Oklahoma), there was an implication that Congress would act to clean all of this up. Three years have gone by and Congress has failed to do anything. This has left the tribal nations, the state of Oklahoma, and the City of Tulsa to pursue clarity around these questions through the other mediator at our disposal: the courts,” Bynum wrote on Facebook. “Over the last few years, the City of Tulsa has been seeking clarity on a seemingly basic issue: do city ordinances apply to everyone in Tulsa? The city’s attorneys interpret federal law to say they do, and the federal district court agreed with them. Attorneys for a tribal citizen disagree, and the federal court of appeals agreed with them. This leaves us one last venue to clear it up: the United States Supreme Court.”

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt issued a statement Wednesday about the 10th Circuit’s decision, saying undermines the City of Tulsa and its ability to enforce laws.

“Citizens of Tulsa, if your city government cannot enforce something as simple as a traffic violation, there will be no rule of law in eastern Oklahoma,” Stitt said. “This is just the beginning. It is plain and simple, there cannot be a different set of rules for people solely based on race. I am hopeful that the United States Supreme Court will rectify this injustice, and the City of Tulsa can rest assured my office will continue to support them as we fight for equality for all Oklahomans, regardless of race or heritage.”

Muscogee (Creek) Nation Principal Chief David Hill responded to Stitt, saying race has nothing to do with the issue at hand and noting that a long-standing cross-deputization agreement with the Tulsa Police Department allows traffic cases involving tribal citizens to be adjudicated in Muscogee Nation District Court.

“It’s unclear to me whether the governor’s remarks are born of intentional dishonesty or an inexcusable ignorance of the laws. But either way, he should be ashamed. The people of Oklahoma deserve better,” Hill said. “There is no law that Tulsa PD can’t enforce. That’s the part Stitt keeps ignoring as he perpetuates needless attacks on tribes — more is more. The city of Tulsa and the MCN have been working together under a cross deputization agreement since 2006. The sky is not falling. We know what to do, the 10th Circuit opinion helps solidify that. When tribes are empowered and municipal partners work with us, communities are safer.”

Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton also released a statement on the 10th Circuit decision.

“The court’s ruling today affirms what we already know: Under the McGirt decision, Indian people accused of crimes on reservations are subject to prosecution from the federal government or tribal courts, not states and cities,” Batton said. “We strongly believe in appropriate punishments for people who break the law, just as we believe it is important to maintain tribal sovereignty by respecting the U.S. Constitution and the laws passed by Congress.”

(Update: This article was updated at 12:12 p.m. Friday, June 30, to include information related to Tulsa Mayor G.T. Bynum’s statement.)