As part of an ongoing legislative push to expunge racist language from land records, Sen. Kristen Thompson is running a bill that would allow municipalities to remove discriminatory covenants from existing neighborhood plats.

Although a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court decision declared such language unconstitutional and unenforceable, many land documents created for older neighborhoods still state that Black people are not allowed to own certain properties.

Senate Bill 1617, which advanced out of the Senate General Government Committee by a 10-0 vote Feb. 8, would create a process for city planning commissions to remove racist or discriminatory language from existing subdivision plats.

“It was a request from the City of Edmond,” Thompson (R-Edmond) said of the bill. “We had found through some of the existing plats that there was some language that we needed to take out because it was discriminatory.”

Edmond mayor: ‘It hurts me. It hurts me everyday.’

Thompson’s bill is particularly applicable for the city of Edmond, although racially restrictive covenants linger in communities across the state and nation.

Racially restrictive covenants and other outgrowths of racism largely prevented Black people from living in Edmond for much of the 20th century. According to the Edmond History Museum, Edmond’s first housing addition platted with a racially restrictive covenant was the Highland Park Addition in 1907. Excluding the Edmond Highway Addition in 1924, every neighborhood platted in Edmond from 1911 until 1949 contained a racially restrictive covenant.

Prior to statehood, several Black families lived in Edmond, according to the Edmond History Museum. African Americans first settled inside Edmond city limits in 1891 near West Edwards Street. A segregated school opened at 21 W. Edwards St. in 1892, and a Black church was established at 31 W. Edwards St. in 1901. According to the Edmond History Museum, the school closed in 1905 owing to a lack of available students.

In September, the city paid homage to Edmond’s early Black history with the installation of the “Bridge of Brotherhood” sculpture at the corner of West Edwards Street and North Broadway.

However, Jim Crow Laws were enacted immediately after Oklahoma became a state in 1907. By 1910, only two Black families lived in Edmond. About a decade later, the Ku Klux Klan established a chapter in Edmond, citizens began promoting Edmond as an all-white town, and it was widely recognized as a sundown town — meaning Black people faced intimidation and threats for being visible in the community after sunset.

By 1920, no Black people lived in Edmond, according to the Edmond History Museum. It wasn’t until the 1970s that another Black family moved into the city limits.

For each of the past two years, the Edmond City Council has included “support legislation to allow for the expungement of discriminatory restrictive covenants from public plats” in its annual legislative agenda.

Edmond Mayor Darrell Davis, who became the city’s first Black mayor after being elected in April 2021, discussed SB 1617 at the Oklahoma Association of REALTORS’ Capitol conference Wednesday.

Davis said families buying properties in 2024 should not have to see racist language lingering in land records for the house they just bought.

“How do you think that feels that if you go buy a piece of land, and all of a sudden you see on the plat, ‘Old Edmond says we wouldn’t sell this to you because of the color of your skin?'” Davis asked. “Do you know what that does to the mental health capacity of individuals? It hurts. It hurts me everyday.”

SB 1617 would allow municipalities to “amend an existing plat which was previously filed with the office of the county clerk of the county where the addition is located to remove an illegal discriminatory restrictive covenant pursuant to the Fair Housing Act.”

At least 30 days ahead of a planning commission meeting where such an amendment would be considered, SB 1617 would require a municipality to notify all property owners in an addition about the city’s effort to remove the language. After being approved by a planning commission, a municipality’s governing board — such as a city council — would need to approve the amended plat for it to be filed on record with the county clerk “against all parcels within the addition.”

Davis said Thompson’s bill is an important companion piece to a law passed last year allowing individual property owners to repudiate discriminatory language within their land records by filing a declaration with the county clerk.

“We now have the ability to take it off, and now we’re working on language for the city to take it off, which needs to be done,” Davis said.

Davis said Realtors play a critical role in who moves into Edmond and the community’s makeup.

“You direct them to what school they go to, you direct them to what type of housing they live in, you direct them (as to whether) they live on the east side or west side of the tracks,” Davis said. “So, you all have a very important part to that, and that’s very important for Edmond to get out of this shadow that we have of being a discriminatory community. Yes, Edmond has its past, just like a lot of communities have. But me as the mayor? We’re not going to forget it. We’re going to remember it, build off of it, and go forward. So we have to take that language off.”

Referencing the outcry in response to a housing assessment Edmond received in August, Davis said housing discrimination still exists today, particularly regarding income levels and housing unit types.

“It was amazing that people stood in line to complain,” Davis said. “Basically they said, ‘If you can’t afford to live in Edmond, we don’t want you here.’ We have to change that mentality. (…) What I’ve been trying to do as mayor is show that Edmond is a welcoming community. I don’t care what you look like, I don’t care where you’re from, I don’t care who you root for. You’re welcome in Edmond.”

Follow NonDoc’s Edmond coverage

‘A big step in the right direction’

Rep. John Pfeiffer authored House Bill 2288 last session to allow Oklahoma property owners to repudiate discriminatory language within deed restrictions by filing a declaration with their county clerk. That law officially took effect Nov. 1.

Now, Pfeiffer is the House author on SB 1617.

“I think this is an important step to allow us to just speed up this process and get this language that isn’t enforceable out of these records,” said Pfeiffer (R-Orlando). “This is going to build off what we started last year.”

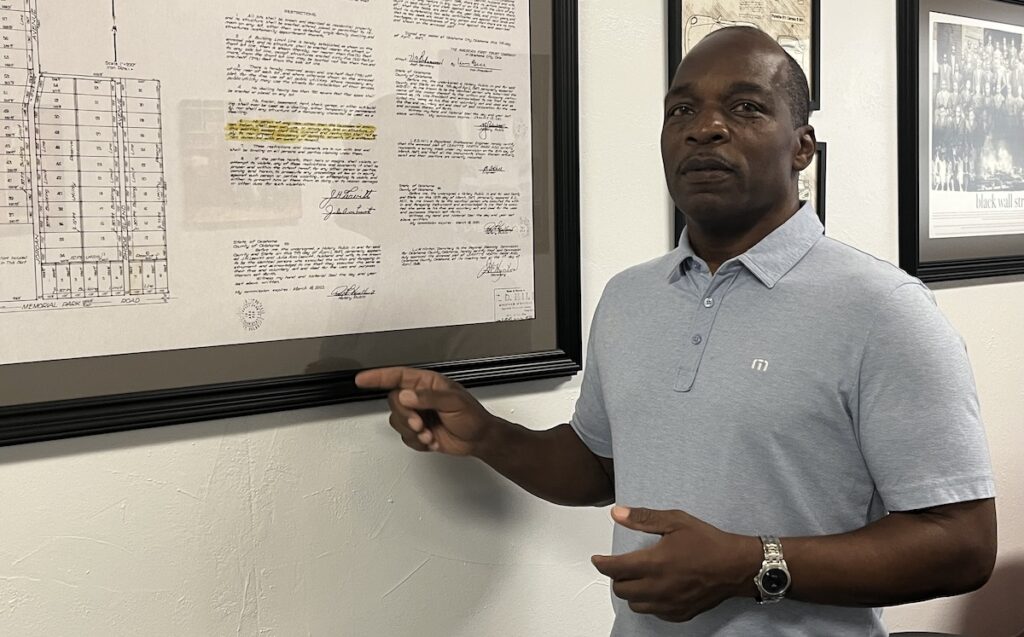

Pfeiffer said he filed HB 2288 after learning about racially restrictive covenants in a NonDoc article about Wayne Frost, a Black Edmond businessman who came across a racially restrictive covenant on his business property’s plat while seeking to expand his auto accessory business.

“This is a good follow-up,” Frost said of SB 1617. “I think this is what we’ve been working toward — to get this into the mainstream to make it easier to remove.”

Frost called SB 1617 a “a big step in the right direction.”

“At my age, from what I’ve seen and experienced over the years, any step forward is good,” Frost said. “Laws don’t change people’s hearts, but this is still a big step in the right direction. This racist language is coming from people’s hearts. This is what they felt. This is what they thought. Hopefully, over the years their hearts have softened, and they don’t have that same hatred for someone because they’re different than you.”

Sen. George Young, who serves on the Senate General Government Committee, signed on as a co-author of SB 1617.

“It’s just another one of those things that the sooner we get it cleaned up and clear it up, the better it is,” said Young (D-OKC). “I don’t want my children or grandchildren even reading that kind of stuff.”

Young grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, during the Civil Rights Movement.

“I think that’s one of the reasons I’m so intent about these kinds of things — getting them changed, getting them corrected,” Young said. “I have seen what we’ve tried to do as far as racial reconciliation, what it’s about, what we’re trying to get, and then making the moves to try and bring true equality in a real way.”

Young said SB 1617 can provide a history lesson for younger Oklahomans.

“These kinds of things are always useful and good, and we’ll make some more progress because we’ll have a chance to talk about them and the fact that they actually existed in reality,” Young said. “A lot of folks — they don’t think we’re making it up — but they think, ‘Oh, that was years ago. It had nothing to do with us.’ But it’s still in [land records].”