Oklahoma County needs a new jail, and voters approved $260 million in bonds to pay for it in 2022. Two years later, however, that amount represents less than half the current projected costs of a facility originally sold to voters as a $300 million project. Instead, that price tag has ballooned to $610 million, and the ultimate impact of inflation remains unknown as a complicated court case pitting Oklahoma County against Oklahoma City continues.

What’s more, even if it gets built, the new jail is expected to cost more to operate than the current facility. The multi-faceted problem has normally tax-averse public officials thinking about raising money either through sales tax or property tax hikes. Others are saying they told you so.

The new county jail is set to open sometime in 2027, but that feels more aspirational than realistic as the final quarter of 2024 approaches.

In June, the OKC City Council denied a request to rezone land at 1901 E. Grand Blvd. that county officials want to use as the site of the jail and a new mental health facility. Not long after, the county purchased the land for $5.4 million and took the city to court, asserting that a county’s constitutional sovereignty makes municipal zoning moot. Recent overtures from the county to the city council to resolve the issue out of court have not been fruitful, and a pre-trial conference is scheduled for Tuesday, Jan. 23.

Del City officials and residents have mounted a ferocious opposition to the site, fearing that detainees will be let out of jail near hundreds of nearby homes.

As all of that plays out, federal American Rescue Plan Act deadlines draw closer. County officials have until Dec. 31 to encumber approximately $40 million of ARPA funds, which they will have to spend in the next two years or risk having it clawed back.

Stakeholders also fear that if the new jail doesn’t get done, the U.S. Department of Justice may step in and force the county to build a more expensive jail, with the cost being passed directly to residents through increased property taxes. The DOJ has been closely monitoring the jail since 2003.

“If we don’t solve this, if we don’t fix it, nobody gets a say because the DOJ will come in and force it down our throats, and it will come with a 30 to 40 percent increase in property taxes,” District 3 Commissioner Myles Davidson said.

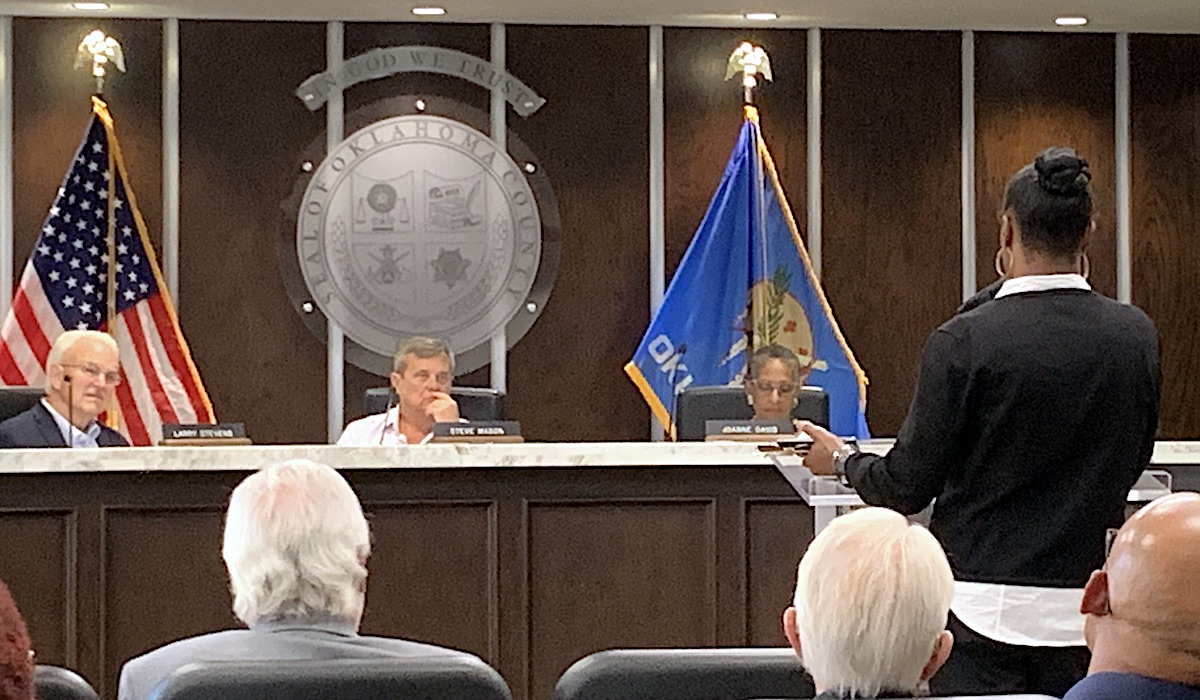

Those fears were echoed by Oklahoma County Bond Oversight Committee Chairman Steve Mason at the Sept. 3 Board of County Commissioners meeting.

“The DOJ building a jail will be a lot more expensive than (county engineer) Stacey Trumbo building a jail,” Mason said.

Oklahoma County’s history with sales taxes

Oklahoma County is unique from the rest of the state in many ways. The state’s laws are made here. It’s home to an NBA team, and about 1.4 million people find it a desirable place to live. It’s also the only one of Oklahoma’s 77 counties that doesn’t have a sales tax.

Decades ago, county governments relied solely on property taxes to fund their operations, but beginning in 1984, counties throughout the state started adopting permanent sales taxes through elections. Oklahoma County never joined the club.

But the county has had a sales tax before. Ironically, it involved the current jail. A temporary 1-cent sales tax approved by voters provided funding to build the current jail, which cost $52 million, opened in 1991 and has been plagued by problems ever since.

“They did a penny for a year in 1988 or 1989, and that’s what constructed our current jail, and it was built to fit a budget,” District 2 Commissioner Brian Maughan said. “They cut a lot of corners to fit the budget, and there was no follow-up revenue for maintenance.”

District 1 Commissioner Carrie Blumert’s time in office ended Monday when she officially stepped down to become CEO of Mental Health Association Oklahoma. Looking back on the jail’s history earlier this fall, Blumert said the lack of a sales tax has been problematic.

“I think as a county, we’ve been at a little bit of a disadvantage that there’s no county sales tax,” she said. “If you look at what Tulsa has been able to do with [its sales tax], it helps with (jail) operations quite a bit.”

Every dollar spent in Tulsa County generates 0.36 cents in county sales tax. In Cleveland County, that rate is 0.12 cents.

Oklahoma City levies 4.12 percent on purchases, and the state sales tax is 4.5 percent.

A multi-faceted approach could bridge funding gap

The funding gap for the new jail has only been growing. Plans call for an 1,800- to 2,400-bed facility, but current funding would fall well short of building a jail that size. The maximum amount of bonds the county can issue is about $480 million, Trumbo told commissioners Sept. 3.

Mason said an 1,800-bed facility would cost about $610 million to build, more than double the original estimate.

“County voters three years ago approved $260 million for a new county jail,” Mason said. “With that amount of money, it would build approximately 700 beds today. Obviously, with the current count last week (…) of about 1,600 guests, that is inadequate. I think the consensus seems to be not to build 700 beds.”

Mason has chaired the committee for about 18 months and has been involved in numerous OKC-area building projects. At the pivotal Sept. 3 meeting, he told commissioners his committee would consider an array of options to raise the additional funding. That could include a 1-cent sales tax, raising property taxes, or a public-private partnership that would essentially act as a loan the county would have to repay.

“What we’re asking is that you guys authorize Stacey (Trumbo) to start working on this public-private partnership RFQ and, also, we’re going to start studying a county-wide tax increase to include ad valorem or sales tax. We’ve got to find the money to build it because with the money we have, we’re not going to build a new jail,” he said.

At least initially, the property tax increase appears to be the least appealing to commissioners. Maughan has long been an opponent of increasing property taxes, also known as ad valorem.

“I just think it’s difficult for people that are on fixed incomes,” Maughan said. “They already have to wrestle with increased cost of living. Insurance and utilities have gone up. So, property taxes are just one more thing. There are people who are home-free on their mortgage and on a fixed income, but they still have property taxes. To have that increase too, that’s difficult.”

Davidson said in early conversations about increasing property taxes, area leaders were cold to the idea. For instance, Edmond voters are being asked to raise their property taxes Nov. 5 with a general obligation bond proposal for street, park and public safety projects.

RELATED

New Oklahoma County Jail soap opera hangs on a cliff by Matt Patterson

“I just don’t see it as something that will be very well received,” Davidson said. “I’ve spoken with community leaders, some in Edmond, and it was a nonstarter for them. I think it was something like four-to-one against it just based on the limited conversations I’ve had with people so far.”

Davidson said exploring a public-private partnership or a sales tax are the most attractive options.

“When the current jail was funded, it was a temporary 1-cent sales tax, and that’s how they got it built,” he said. “We may be able to also get some funding from a public-private partnership. In that scenario, the county would own the jail, but the financing would in effect be a loan.”

Davidson said while the 1-cent tax would be temporary, a half-cent (or less) sales tax could be a permanent option to fund jail operations after the 1-cent tax expires.

Blumert had also supported the sales tax option, though it would now be from the sidelines simply as a voter.

“When and if this goes on the ballot, I’ll be voting as a private citizen,” Blumert said. “I will vote for it, whether it’s a permanent or temporary sales tax. But it’s my preference that it’s a permanent sales tax to support the operations of the jail.”

A property tax increase would be a burden that would be shouldered exclusively by county residents. A sales tax would impact anyone who comes into the county and spends money.

“I think there have been some studies by economists that have shown about 40 percent of our local metro area sales taxes are collected from people passing through,” Maughan said. “These are not residents. And so, if we have to go to the public for some financing, I would prefer a way that isn’t as punitive and is underwritten in part by people who are passing through versus people — just our people — who live here.”

The public-private partnership option is more complicated and would require the county to make payments over more than two decades, but it would also leave residents unburdened by tax increases.

“The way it works is you have to put the specs together to showcase to would-be vendors who might bid on it,” Maughan said. “It would have to be from a lending institution. I don’t know if that is doable within our existing budget and our projections for future budgets. So, I think we have to put together what we’re asking them to bid on, and then we would have to wait for those proposals to come back from any interested vendors, who would then tell us what the fee schedule would be and how much they would charge for their services. And if it doesn’t yield enough to be worth it, then that might be a policy decision to not pursue that any further.”

Mason’s committee is also studying using portions of existing property tax revenue to fund part of the new jail.

“Every year, the county receives additional ad valorem taxes, which they then put in the budget,” Mason told commissioners Sept. 3. “Last year, it was $6 million. This year, it sounds like it’s going to be about $2 million. And say we’re going to take that $2 million, and, rather than put it in the county budget, we’re going to take $2 million for 25 or 30 years and put it in a lockbox to pay back the bonds and use it as a source of collateral.”

Maughan said the excess property tax revenues could not cover the entire project, but they could fund some of it without asking voters to approve new bonds.

“We believe that is an option — to take some money and put it in a lockbox and bond against it,” Maughan said. “So that would be an outside-the-box approach to fundraising some of the gaps without having to go to voters for additional requests for funds.”

That could be part of a multi-faceted approach.

“It could end up being a combination of several things,” Davidson said.

New jail will likely cost more to operate

The county spends about $36 million to operate the jail annually, which includes food and medical care for detainees. But the new facility is expected to cost more to operate. Its direct supervision model will require more staff, and costs for everyday things — ranging from lettuce to toilet paper — have gone up in recent years.

When the county built the current jail, some of its operating cost was expected to be offset by housing federal detainees. But with the DOJ began monitoring the jail for two decades, those funds dried up.

“We currently don’t have enough money to appropriately operate the current jail,” Blumert said. “So, in a new facility, you’re still going to have the issue with not having enough operational money.”

That’s one reason the commissioners are considering a permanent sales tax to support jail operations, something dozens of other Oklahoma counties already have.

“I don’t know what the number is, whether it’s tied to a quarter-cent, a half-cent or a full cent, [but] I think the jail needs more ongoing operational funding,” Blumert said. “I mean, if we want to provide a higher level of medical care and more programming and more support to detainees, we’re going to need more funding.”

Maughan said inflation will make the new jail cost more to operate.

“My concern is that costs have gone up so much,” Maughan said. “It’s not the same as it was when we went to voters two and a half years ago. We’re looking at a drastically different operation model. Food has gone up. Medical has gone up. I’m concerned about the construction costs being so different, but also the operational costs are going to be different, and the county is really feeling the pinch like the rest of the country.”

Davidson said those increased costs are one reason why a permanent sales tax to fund jail operations might be part of the approach in the long term.

“That’s going to be one of the challenges we face — making sure that when this jail is built, we can run it the way it’s supposed to be run without some of the problems with long-term maintenance we’ve seen with the current jail,” Davidson said.

In his view, Davidson said one of the most critical aspects of the entire process must be avoiding the same mistakes that were made three decades ago with the current facility that was over budget and has been plagued with problems since even before it opened.

“We are exploring any and all avenues available to the commissioners in order to not repeat the mistakes of the past,” Davidson said.

Bana: ‘We don’t need that big of a jail’

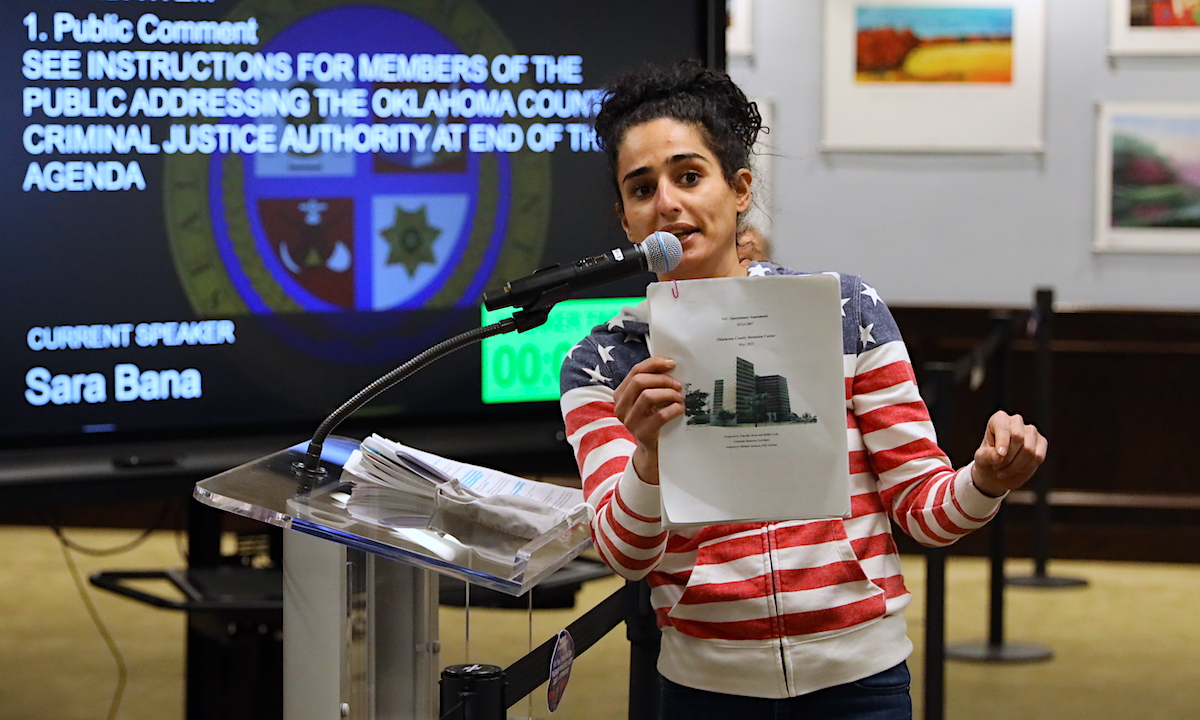

Midwest City City Councilwoman Sara Bana is one of many people unsurprised to see the new jail project in rough straits.

Bana, who announced she is running for Blumert’s seat via Facebook on Sept. 10, has been a longtime critic of both how the county manages the current jail and its plans for a new one through her work with the People’s Council for Justice Reform. Based on data she has seen from the National Institute of Corrections, Bana said the cost estimated for the planned jail would cost from $600 million to $800 million.

“The Board of County Commissioners, at the jail trust meetings, they were calling us uneducated fools,” Bana said. “(Former Commissioner Kevin) Calvey was still there, and they weren’t taking us seriously. We were telling them it was going to cost more than what they were saying it would. To me, it’s just not truthful that they’re trying to spin this as they didn’t have any understanding of what the numbers to build such a facility would be. Either that, or they were scheming and scamming the taxpayers of Oklahoma County again. They proposed a $260 million bond knowing it wouldn’t be enough, or they hoped it would be low enough to get a ‘Yes’ vote, and then they would go through the backdoor to get the rest of the additional revenue.”

Bana also believes the current plan to build a jail with at least 1,800 beds — and possibly as many as 2,400 — is excessive. She said only those who are a threat to others should be in jail.

“We don’t need a facility that large,” Bana said. “If they wanted to be proactive on justice reform and public safety, we have the capacity to reduce the jail population to 600 to 800 [people]. The individuals that need to be housed there are violent offenders. The county jail has no business contracting with municipalities for petty offenses simply because municipalities want to contract with them.”

Bail reform could also help reduce the jail population, she said.

“We have the capacity to use ankle monitors to release people until they access due process,” Bana said. “That would eliminate some unnecessary population. Ending cash bail would also help reduce the jail population, but that would have to come from a legislative effort. The bottom line is these conversations could be happening, but they’re not.”

Bana believes the new jail will require sales tax revenue to fund both its construction and operation, and she has grave concerns about the county government’s ability to put it to the best use.

“I’m a person who truly believes in the role of government as far as building roads and bridges and other infrastructure and all of the other things government can do to provide health and public safety, but I don’t think the government has been good stewards of taxpayer dollars, and I think that has created a level of distrust,” Bana said. “So given that, I don’t think I could support a sales tax, because I don’t trust the people who have the reins now to be responsible with the money.”

View renderings of the proposed jail and behavioral health center