Imagine it is the early 1950s, and you are preparing to board a Greyhound for a three-hour trip. You need something to help pass the time. At the bus station kiosk, you spot a rack of paperback novels, and one of them catches your eye, perhaps because its cover suggests some sort of sleazy mayhem, or because it only costs a quarter.

You buy it to read on the bus. It is a first-person narrative about a guy with a few screws loose, and there is a sexy, sneaky dame. Some ordinary stupid people from somewhere in Texas pop up from time to time.

You finish the novel, notice that it was written by somebody named Jim Thompson, and decide that the story was pretty weird. You say, “huh,” and toss the book aside. You think maybe you should have bought something by Louis L’Amour.

Thing is, Thompson’s novel keeps coming back to you. It does to your brain what a bowl of bad chili might do to your intestines: It wakes you up in the middle of the night and conveys a certain sense of urgency.

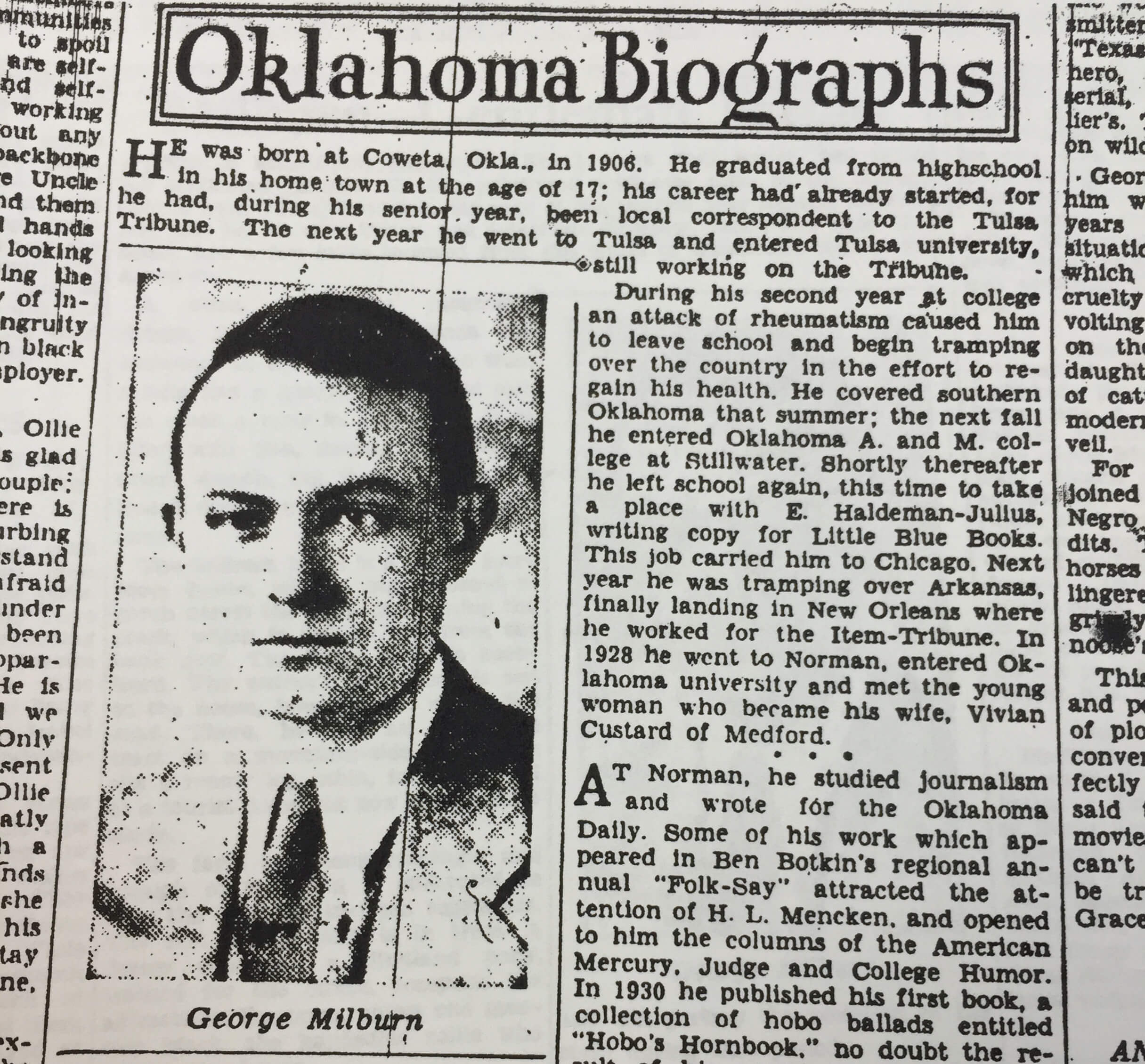

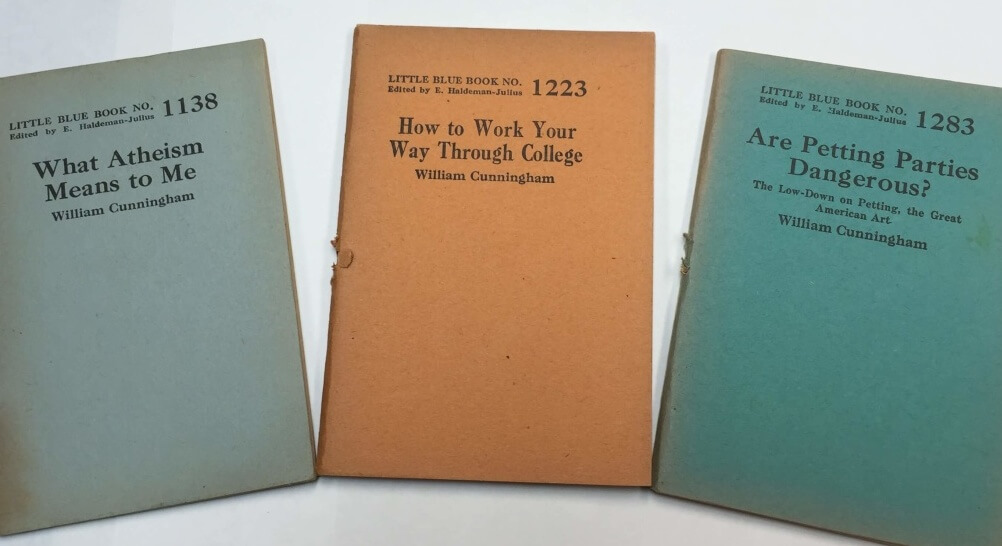

Jim Thompson was born in Anadarko in 1906 and reared in several other places. His formal education was sporadic and erratic. He did whatever jobs there were to do, whatever was needed to put food on the table. He was a jack-of-all-trades and a master of writing. In Oklahoma City, he met George Milburn and William Cunningham, working for Cunningham at the Oklahoma Federal Writers’ Project and being named by Cunningham as his successor when Cunningham went to D.C. to direct the entire program. But Thompson had joined the Communist Party in the 1930s, and that was enough to get him ousted. (Zoe Tilghman, again, don’t you know. She did so much and worked so hard to make certain that Oklahoma’s best writers of the 1930s would be ignored and forgotten in their native state. What a great lady.)

RELATED

“Meet George Milburn, a forgotten Oklahoma writer” by William W. Savage, Jr.

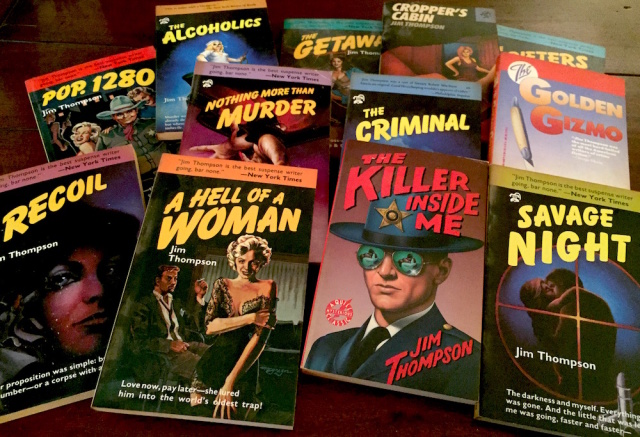

Thompson went back to odd jobs — odd writing jobs. In his 71 years, he wrote about 30 novels, paperback originals that were soon out of print in America but alive and well in Europe. The French in particular admired Jim Thompson’s work. The guy produced hard-boiled existential noir, and his name would be mentioned in the same breath as Dashiell Hammett, Albert Camus, Raymond Chandler and Jean-Paul Sartre. Titles like A Hell of a Woman, Nothing More Than Murder, The Criminal, Savage Night, Recoil and The Alcoholics suggested to the French a certain je ne sais pas de quoi, one supposes.

Thompson worked for newspapers on both coasts, and in Hollywood he wrote a couple of screenplays for Stanley Kubrick (The Killing and Paths of Glory) because Kubrick was a big fan. So was Sam Peckinpah, who filmed Thompson’s 1958 novel The Getaway in 1972. For no reason whatsoever, Roger Donaldson directed a scene-for-scene remake in 1994, but neither film covered over half the novel, perhaps because what happens in the second half depicts the criminals’ version of hell on Earth, from which nobody gets away. French director Bertrand Tavernier filmed Thompson’s 1964 novel Pop. 1280 as the movie Coup de Torchon (also known as Clean Slate) in 1981, setting it in 1930s Africa instead of Thompson’s Pottsville, which was located somewhere in the Southwest.

Perhaps Thompson’s best-known (and arguably his best) novel is The Killer Inside Me, published in 1952. It was Thompson’s personal favorite, and a couple of filmmakers have tried to put it on celluloid; Thompson’s fiction simply defies film. The pictures he puts in your head are more vivid — and disturbing — than the ones other people put on the screen.

Well, OK, maybe Stephen Frears’ The Grifters (1990), based on Thompson’s 1963 novel of the same name, comes close. But close doesn’t really count too much when it comes to Jim Thompson.

Two items sometimes mentioned as autobiographical novels appear in Thompson’s bibliography: Bad Boy (1953) and Rough Neck (1954). You might also read Robert Polito’s Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson (1995).

And you can make what you will of the contradictions, because Thompson the man was nothing like anybody in his novels. Yes, he drank like a fish and smoked like a chimney. He stood six-foot-four and weighed 250 pounds, but a gentler soul would be hard to find. He was married to the same woman for 46 years. Arnold Hano, Thompson’s friend who wrote his obituary for the Los Angeles Times (May 1, 1977, p. 3) called him soft-hearted and soft-spoken. “I never heard him use a dirty word,” Hano wrote. “I never heard him tell a salacious story,” even though his novels were full of both.

RELATED

“Commie symp author accomplished much for Oklahoma” by William W. Savage, Jr.

Thompson told Hano the story of his father’s death in 1941. In a facility for alcoholics, the elder Thompson was about to be evicted because he could no longer pay for his care. He wrote to his son asking for help. Jim Thompson obtained the money by asking publishers to lend him a typewriter and some paper. Finally, a small paperback house did, and Thompson wrote a novel in a few days. The publishers bought it on the spot, and Thompson sent the money to his father. The whole process took 10 days, from asking for a typewriter to writing a novel to sending the money to his father.

By the time the money arrived, Thompson’s father had pulled the stuffing from his mattress and forced it down his own throat until he died. Years later, Thompson would still cry about that. Had his father not trusted him?

Thompson suffered some small strokes in his late 60s, and in a couple of years he was physically unable to write. It had been his custom to write eight hours a day. He could no longer do it. So he stopped eating. He starved himself to death in the late spring of 1977. That may not be the official version, but his widow believed it. Several of his friends believed it.

Read his novels, and you will believe it, too.