Oklahoma produced several writers of note during the 1930s, when the state was thought to yield only dust and immigrants. Most of them were born in small towns in what was not yet Oklahoma. They obtained college educations. And they left the state.

Oddly, they are largely forgotten, in a place constantly in search of something to be proud: sports teams, one skyscraper to break the horizon, a partially re-named river and so forth.

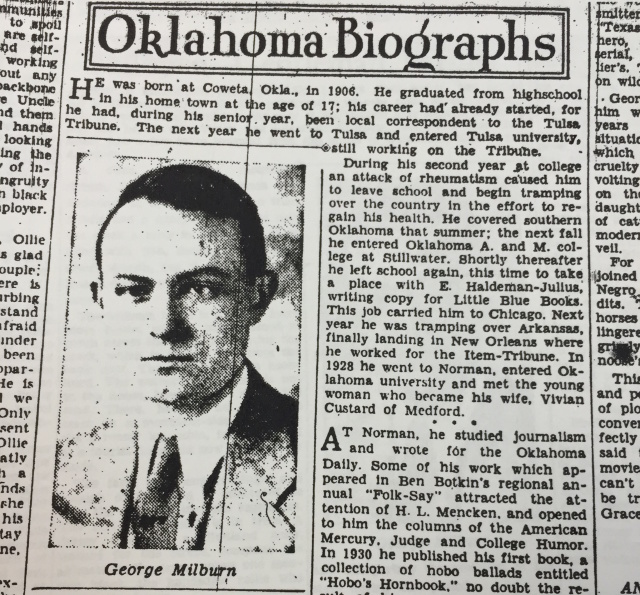

Thus, meet George Milburn, born in Coweta in 1906. By the time he was 16, he was working as a newspaper reporter, a job he maintained as a student at the University of Tulsa. Then, he spent a year at Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University, and Cowboys, not Aggies) before dropping out and hitting the road.

Oklahoma was smack in the middle of an agricultural depression — too much wheat and cotton after World War I caused markets to fall dramatically — years before the capital-G Great Depression of the 1930s; and Milburn thought perhaps the grass was greener in Chicago. He bummed his way there and found work freelancing for a paperback publisher, writing such ephemera as “The Best Jokes About Drunks,” “The Best Hobo Jokes,” “A Handbook of Amateur Magicians,” and “How to Tie All Kinds of Knots.”

By 1927, Milburn was on the road again. In 1928, he enrolled in the University of Oklahoma, but Norman would see the last of him in 1930. He took to roaming once more. Except for a few years here and a few years there, he remained an itinerant writer until a pickled liver and a bum ticker conspired to kill him in 1966.

Milburn published in Harper’s and Vanity Fair, Scribner’s and The New Yorker, among other periodicals. In 1931, he published a collection of short stories entitled “Oklahoma Town,” and followed in 1933 with “No More Trumpets,” containing yarns about more small towns. It became apparent that he did not care for them.

Literary critics to the contrary notwithstanding (they prefer “No More Trumpets”), Milburn’s masterpiece is “Catalogue,” published in 1936. Set in a fictitious small town in eastern Oklahoma, it concerns the reaction of townsfolk to the annual arrival of mail-order catalogs or “dream books” offering selections revealing the interests and aspirations of those who peruse the bright pages. Structurally, “Catalogue” reminds the reader of Sherwood Anderson’s “Winesburg, Ohio,” but surpasses it in matters ribald and bawdy.

The part about the adulterer sneaking through the banker’s backyard in the dark and falling in the partially filled and under-renovation privy hole — well, that alone is worth the price of admission, if you can find a copy of the book somewhere.

But of course, there is more to it than that, which is why historian Angie Debo wrote that his “photographic accuracy of observation,” his “swift, terse style, and brilliant characterization” were just too much when describing the kind of small town from which she had come. “Naturally,” she said of Milburn, “he is not loved in his home state.”

Well, he should be, now that we’re urban and all.

George Milburn published two more novels, “Flannigan’s Folly” in 1947, and a paperback originally entitled “Julie” in 1956, neither of which received the critical acclaim of his earlier work. He labored as a functionary in the state of New York, and that is where he died.

Search the secondhand bookstores or follow the Amazon.com links. Don’t bother looking him up in Oklahoma history textbooks. He should be there, but he isn’t — like entirely too many others.