During the recent gubernatorial debate, one candidate noted that Oklahoma has a higher violent crime rate than California. The other candidate responded with a snort, a folksy grin and a general expression of disbelief.

How could Oklahoma have more violent crime per capita than California? Doesn’t Oklahoma have permitless open carry so that we can protect ourselves from criminals? Can’t Oklahomans tote automatic weapons in public in the name of Second Amendment protections?

Well, all of that should prompt us to examine Oklahoma’s violent history, which our state’s education system sometimes teaches in bits and pieces, but which we rarely put together as an analysis of the traumas and tragedies that have shaped our land.

Murders, massacres in the Great American Desert

Oklahoma grew from what was intended to be a death camp for Native Americans, who were forced from their ancestral homelands into an area that the military had deemed the Great American Desert, in which, they said, nobody could survive. The designation was made in 1819, and in 1830 came the Indian Removal Act. Put ’em there, Congress figured. They won’t make it. Think of the Trail of Tears — or, rather, the many trails of tears.

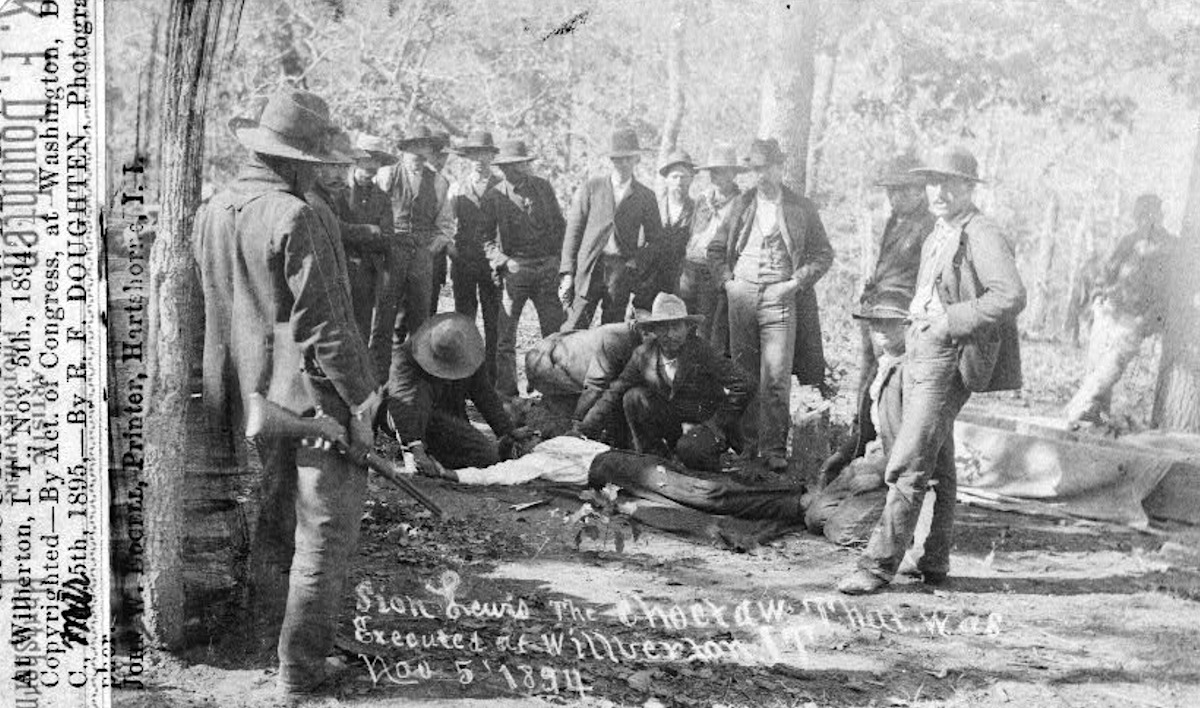

After the Civil War, there was so much violent crime hereabouts that U.S. marshals had to be dispatched from Arkansas to round up felons and take them to Fort Smith for trial and execution. (Federal jurisdiction, anyone?) Tribal nations administered harsh punishments as well, evidenced by The Whipping Tree in the Seminole Nation and the 1894 botched execution of Choctaw citizen Silan Lewis. The Wild West was exactly that, and our future state was one big hideout for criminals who hailed from virtually everywhere.

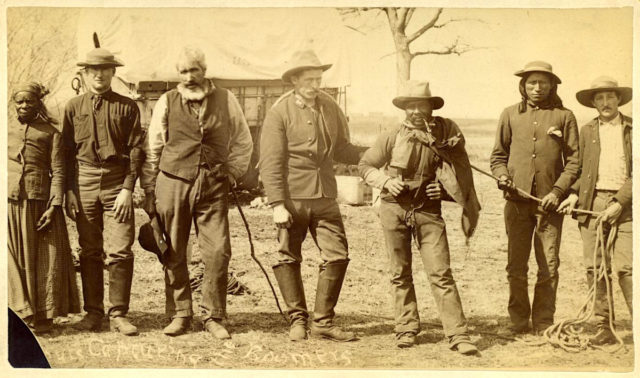

Then came the Boomers, people who saw that the supposed death camp had not worked and that its inhabitants had survived and prospered. Ergo, dispossess the Native Americans again, Congress figured, and open the land for white settlement. The government considered Boomers criminals. The U.S. Army considered their leader, David Payne, certifiably insane.

RELATED

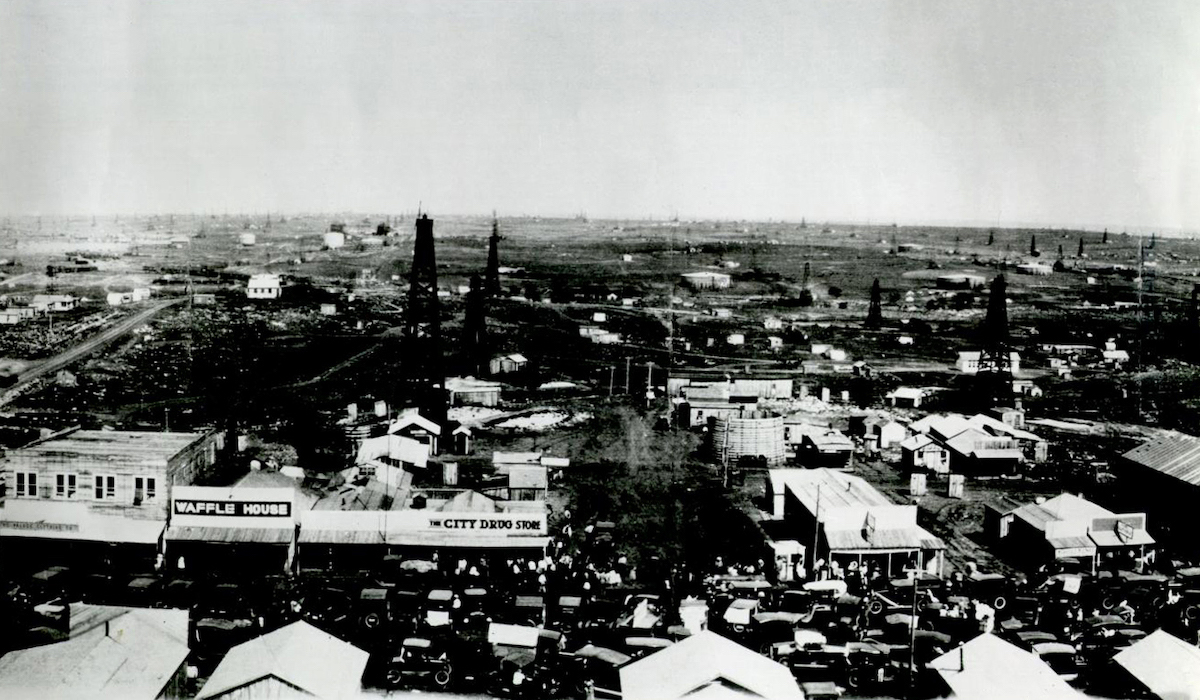

Long gone, Whizbang prospered in the wild days of Oklahoma boomtowns by Heide Brandes

When the federal government decided that things were peaceful enough to create Oklahoma Territory and allow settlers in, the Sooners appeared. They did not wish to wait for any official openings and would try to sneak in early to have the best selection of land. Sooners, like Boomers, were criminals as far as the government was concerned, and yet Oklahomans to this day call themselves Sooners. “Boomer,” yells Billy Sims, and “Sooner” shouts everyone else. We celebrate our criminal past at football games.

Eventually, in 1907, came statehood; a raft of incompetent, corrupt or loony governors; the Ku Klux Klan watching out for what it considered inappropriate behavior and punishing it accordingly; the Osage Indian murders; the Tulsa Race Massacre née Riot; and the Great Depression, with its local hero Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd (and passersby like Bonnie Parker, Clyde Barrow and Machine Gun Kelly); et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Ignorance of state history has served us poorly

If it feels like I am breezing through a laundry list of distasteful and traumatic components of Oklahoma history, pardon me. I taught the stuff for 40 years, and I was often perplexed by how many graduates of Oklahoma high schools had never heard much about any of it.

I suppose that means I should not be surprised these days when our incumbent governor expresses disbelief about our crime statistics. Nor should I be shocked when his chief challenger seeks political points by criticizing the historic 2019 mass commutation that granted hundreds of people a second chance at freedom. We spent decades locking up as many folks as we could, and there’s nothing like a heated campaign for governor to fill the airwaves with fear-mongering, crime-related advertising.

When those messages are interspersed among daily TV news broadcasts that focus on shootings, stabbings, car jackings and executions, who needs to argue about prosecutorial jurisdiction over the former death camp?

Now that I think about it, perhaps I should pause before writing any future pieces that emphasize the influence of Oklahoma’s violent history, lest the state Legislature — whose historic members have fought, battered and shot at one another in chambers — decide these sordid details should be stripped from the state curriculum or banned under a broader prohibition against anything that makes one vexatious.

Of course, I am reminded of what the philosopher George Santayana said: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

For the politicians out there, let me ask a related question: If you cannot remember Oklahoma’s violent history, what influence can you have on the future?