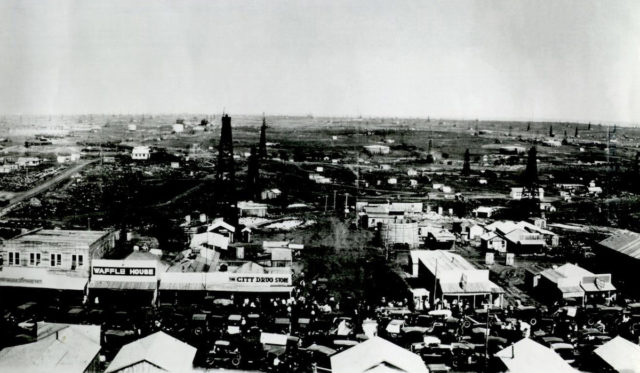

OSAGE COUNTY — In 1920, oil was discovered near Burbank, Oklahoma, east of Ponca City. Almost overnight, hundreds of boomtowns sprang up in the area — roughshod places filled with hungry men looking to make their fortunes in the oil fields.

Those hungry men were also reckless risk-takers who sometimes tiptoed — or stomped — onto the wrong side of the law, and the towns they established were rowdy, dangerous places, where murder and robbery were as common as a shot of whiskey.

Perhaps the wildest of these towns was Whizbang, about four miles north of Burbank in Osage County. The town’s lawlessness was so notorious, messengers on their way to and from the local oil fields were known to “gallop at full speed without stopping to get safely through the rowdy town,” according to the Osage County Historical Society.

Whizbang had a short but fiery history, replete with violence and chaos, as did many of the dozens of oilfield boomtowns that sprang up during those years. If it weren’t for the uniqueness of its name, Whizbang may have slid into the muddy ditches of forgotten history like so many of the other towns, but a name can make a place memorable.

Today, Whizbang is little more than a few rocky ruins outside Pawhuska. Its glory days are a fading memory, but it serves as a dramatic example of what life was like when black gold bubbled out of the ground and changed the history of Oklahoma.

The birth of Whizbang

Oil has always lurked beneath the soil of Oklahoma. Native American tribes were well aware of the black goo, but, according to Larry O’Dell, director of communications and development for the Oklahoma Historical Society, the tribes paid the stuff little mind, since they had no real use for it.

“Right around the early 1900s, I believe in 1906, people started actually pulling it out of the ground,” he said. “Around 1919, oil really kicked off in Osage County.”

Osage County soon became one of the richest, best-known oil areas in the country. By 1930, more than three dozen Osage oil fields existed. Between 1901 and 1930, 319 million barrels of crude were pumped from the ground in the county.

Whizbang was born nearly overnight in 1921 after Ernest W. Marland (who would later become the 10th governor of Oklahoma) hit oil in the area with his 101 Ranch Oil Company, a precursor to Marland Oil Company, which eventually purchased Conoco. Marland’s first well near Whizbang pumped more than 600 barrels of oil a day, and he soon drilled more wells, one of which yielded upwards of 2,500 barrels of oil per day.

The abundant oil attracted not only men looking to work the oilfields but businesses and families as well. By the end of 1921, the town became official with its own post office and featured more than 300 businesses and houses.

It also had an ongoing argument over what to call itself. Legally, the town was called Denoya, the preferred moniker among those citizens hoping the place could preserve some semblance of dignity. But it couldn’t shake the popular nickname of Whizbang.

The name’s origin is disputed. Some believe the Osage coined the term from the noises made by oilfield machinery. The more accepted explanation is that it came from a popular humor magazine called Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang.

“The magazine started in 1919, and many Americans thought it was immoral and corrupt,” O’Dell explained. “And that’s what a lot of the locals thought about these boomtowns.”

The town certainly lived up to its name, becoming notorious as one of the most wild and dangerous communities of the Oklahoma oil boom.

A town of terror

Whizbang came to life around the time of the Osage murders made famous by the book Killers of the Flower Moon, by David Grann. At the same time as the Reign of Terror (as the Osage called the string of murders and assassinations), towns like Whizbang were in a state of lawlessness — full of violence, bootlegging, prostitution and general rowdiness. Residents later recalled that it was not safe for women to go out at night, and gunshots were commonly heard ringing through the streets.

Whizbang became a violent place that attracted desperate people.

In his book Ghost Towns of Oklahoma, John Wesley Morris writes about a man called Jose Alvarado — real name Bert Bryant — who worked both sides of the law in Whizbang. One night, he fought over a woman with a lawman from the nearby town of Shidler. In the scuffle, the other lawman shot the woman in question dead and shot Alvarado in the chest and legs.

Alvarado shot the lawman back four times.

But why should a little thing like a shootout grow into a grudge? The two men were taken to the same hospital to recover, began talking, forgot the woman and became good friends.

“Such was a day in the life of Whizbang,” writes Morris.

Many people came to the boomtowns to make money. Some had legitimate businesses, such as hotels, retail stores and restaurants. Others started illegal empires, specializing in bootlegging, gambling and prostitution.

“Jake joints” sold Jamaican Ginger, an alcoholic product known for causing paralysis in the legs of those who drank too much of it, according to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains.

“In the 1920s, the large oil companies began building camps for workers and families in an attempt to improve living conditions in the new fields. Life in these camps was preferred over the tents or boomtown housing, even though most camps only provided a few rows of houses painted white with green or orange roofs,” the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains explains. “Outdoor toilets were the rule, but even these were unavailable in many camps and towns, leaving people to their own devices, usually vacant lots or empty fields. Contagious diseases, including tuberculosis and diphtheria, spread rapidly in such conditions.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘I was never in my life so scared’

It wasn’t just the violence that made life in Whizbang and similar boomtowns so risky. Men of all ilk flocked to the oil fields in Oklahoma to make their fortune, but the work was just as deadly as it was lucrative.

One person who later attested to this perilous way of life was the actor Clark Gable, who, long before telling Scarlett O’Hara, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn,” worked in the Oklahoma oil fields.

According to a 1983 article from The Oklahoman by Sam Henderson, Gable made his first appearance in Osage County in 1921 and eventually became an apprentice tool dresser — a job that involved pounding a 700-pound drill bit with a 16-pound sledgehammer to sharpen the edges.

“He also climbed a rickety 85-foot wooden tower at night in freezing rain, in bitter cold, in driving winds,” Henderson wrote. “Then he oiled the crown bearings on the rig there in the pitch blackness. ‘I was never in my life so scared,’ he later admitted. ‘Not even when I served in World War II.’”

Another colorful character drawn to the rough and tumble of the boomtowns was Oklahoma vaudeville and burlesque queen Ruby Darby, who made the rounds through the oil towns, performing for roughnecks, though it doesn’t seem she ever visited Whizbang.

“The boomtowns were very exciting cities, but also very dangerous,” said Dale Ingram, who is authoring a book about Darby’s life. “Oilfield work was a dangerous industry because the technology had not caught up with the risk. At the time, they extracted oil by dropping nitroglycerin dynamite into oil wells and timing it so it would explode in the bottom. (…) You had lots of death and injury.”

Ingram said Darby’s recollections of the other boomtowns gave an intimate look at life in these wild communities.

“You had taverns and brothels and gambling and all those things,” Ingram said. “It was a wild time, and Ruby was right in the middle of it.”

From boomtown to ghost town

Like many of the infamous boomtowns, Whizbang ended with a sigh rather than a bang.

Google Map coordinates

As the oil boom subsided through the late 1920s and 1930s, independent contractors and their workers moved out. The oil companies brought in their own workers, who were more reliable and had families, and the chaos began to die down.

“Jobs started to shift from rural to urban. People moved to a city to find jobs,” said O’Dell.

A former resident of the nearby town of Kaw told The Oklahoman in 1998 that she recalled a tornado going through Whizbang sometime in the 1930s and that nobody bothered to rebuild the town afterward.

Officially, Whizbang — or, technically, Denoya — stayed in existence until its post office shut down, on Sept. 30, 1942.

After that, the town became just another empty boomtown destined for ghosthood and urban legends.