Last week, two major journalism organizations in Oklahoma got stories wrong. One pulled its post down without issuing any official correction, while the other updated and noted its error.

Talk about good news / bad news.

When journalists make mistakes, they should be transparent about their errors and issue permanent notice that the error occurred. In one instance last week, an Oklahoma outlet failed to uphold that basic editorial ethic. In doing so, it missed a chance to improve its perception among an increasingly skeptical public.

A disappearing ‘story’

Viewers of TV news and Oklahoma City’s KOCO-5 already have plenty of reasons to be skeptical. We have documented a couple of them.

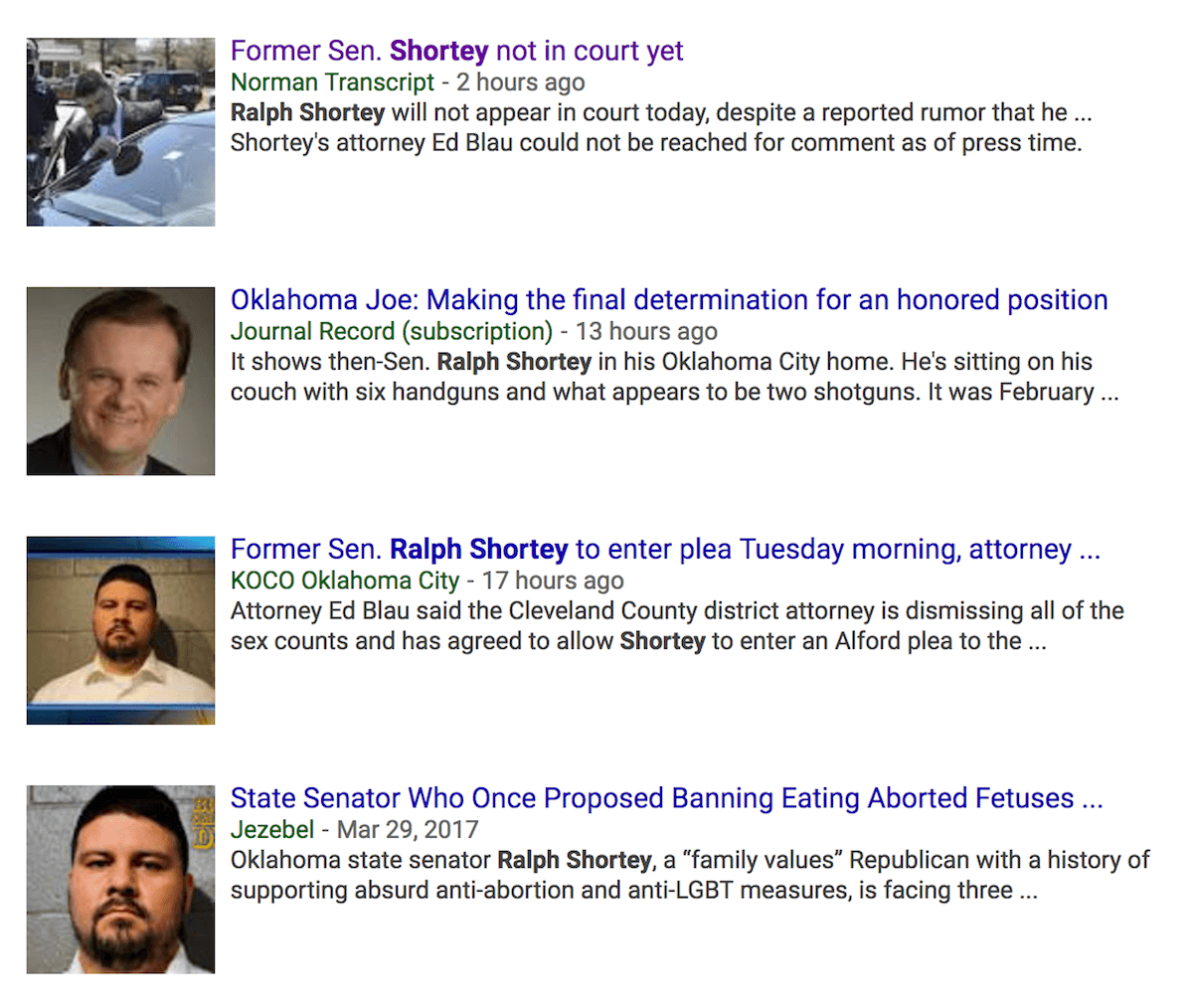

On April 3, KOCO put out a story that can be partially seen in cached Google news results below. It reported that former Sen. Ralph Shortey’s attorney, Ed Blau, said Cleveland County District Attorney Greg Mashburn would be “dismissing all of the sex counts and has agreed to allow Shortey to enter an Alford plea” in his case.

Apparently, however, that may not be what ultimately happens. Hours after KOCO’s story had been posted, it was suddenly unavailable, the link on Google directing to an error page. KOCO’s Twitter said nothing of the incident, and no new article about the Shortey case has been posted as of Sunday afternoon.

The next day, the Norman Transcript published a brief stating that Shortey would not appear in court that day “despite a reported rumor that he had entered into an Alford plea.” The paper said Blau “could not be reached for comment as of press time.”

Readers who had posted KOCO’s original story on Facebook began asking questions about what had happened. People seemed confused. Some questioned whether removing a story entirely was standard within the ethical code of journalism. (No, it’s not.)

The value of corrections

On April 5, the Tulsa World’s regional affiliate, the Skiatook Journal, made a different editorial decision after making a mistake. A story posted mid-morning stated only two voters had cast ballots for a seat on the town of Sperry’s board of trustees.

Quickly, however, someone noticed that Sperry has precincts in both Osage and Tulsa counties. The writer had only checked the Osage precincts, which showed only two votes. In total, 186 people had voted for the position.

The story was not removed but rather changed almost entirely to focus on basic election results. The second paragraph, however, disclosed the paper’s error:

Decisions on the Town of Sperry Trustees and the sales tax proposition were decided by voters April 4.

We originally reported last night that only two voters showed up to the polls. The results have since been updated and show more votes were cast.

While perhaps that statement could have been emphasized a little better with a “correction” at the start of the updated post, the Skiatook Journal — and thus the Tulsa World — at least owned their mistake and did not try to hide it from their readership.

Credibility extra important with ‘fake news’

To that end, journalism outfits should always issue corrections or note an “update” if something even mildly significant has changed in a digitally published post. Corrections are not typically needed when typos are caught, but corrections can be useful even for noting that someone’s name has been misspelled.

We issue corrections fairly frequently at NonDoc. Though sometimes it can feel a bit shameful to have to admit an error in public, we do so with the knowledge that even our detractors are likely to appreciate the honesty. In the end, honesty and transparency are traditional keys of ethical journalism.

Failing to uphold those pillars leaves the entire profession open to critique from readers. Even the president of the United States has launched the phrase “fake news” into the public lexicon as an effective yet inherently too broad critique on media.

Cracked.com published a commentary last week detailing the shoddy ethical decisions made by sites like the Huffington Post, Attn.com and the unabashedly liberal blog Daily Kos. The commentary culminates in breaking down a USA Today headline that implies a great deal more meat than is on its bone.

So, in a world where Americans have a record-low amount of “trust” in journalism organizations and the president is effectively hiding his attacks on the free press behind the inflation of a media victimization narrative, all media who want to be taken seriously need to value their credibility.

An easy way to help do that is to issue corrections when errors are made.

No one ever said journalists have to be perfect. The public just wants honesty.