In a third-floor conference room at the Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association’s headquarters, OIPA president Tim Wigley listened Monday as two oil and gas executives discussed the competition for drilling capital that has overtaken the industry.

“We need capital, and we’re no different than any other company in the oil and gas sector,” Chaparral Energy CEO Earl Reynolds told five assembled reporters. “The (industry’s) volatility has driven capital out of the business. It’s important to note that. Trillions of dollars have left the business. So if I’m trying to access capital, I have to differentiate myself from somebody else.

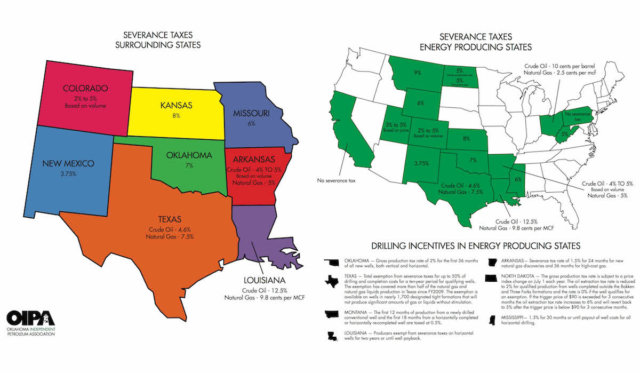

“Our concern would be if we start messing with gross production rates (in Oklahoma), I think it would materially impact our ability to access capital and be competitive in this sector.”

I was seated across from Wigley, listening to Reynolds and Triad Energy co-owner Mike McDonald explain why their companies and many of their colleagues are worried about mounting public pressure to adjust Oklahoma’s 2 percent gross production tax incentive rate. I should know.

Hours earlier, NonDoc had published an editorial I had authored. In it, we argued the results of a poll showing 67 percent support for eliminating the GPT incentive rate meant GOP leadership should put some sort of GPT rate change up for a vote during the state’s impending special session.

“Anyone who thinks this business is thriving is just not informed,” McDonald told the room.

I grimaced in my reading glasses, struggling to see from afar if the veteran businessman was looking at me.

‘They tend to be humble people’

When Monday’s OIPA media seminar turned to questions, I asked Wigley about what seems to be an odd time in Oklahoma politics. Never in my brief adult life have I heard so many Okies calling for the oil and gas industry to pay more taxes. How, I wondered, could OIPA convince the public of the complex and stressful financial situations facing petroleum companies?

“This industry like most natural resource industries (…) they tend to be made up of people who are hard-working and keep their heads down,” Wigley said. “They don’t go hold protest signs. They don’t go scream and yell. They don’t live on the internet blogging. They tend to be humble people, not braggadocios.

“I think this industry needs to do a better job of letting people know what it is we do, how we do it, how we’re regulated, how we’re compliant and the benefits we bring the state of Oklahoma.”

To that end, Reynolds and McDonald offered informative, deep-in-the-weeds examples of the business practices familiar to them but likely over the heads of most non-industry Oklahomans.

McDonald counted up the tax and operating costs associated with drilling a $10 million well. He estimated those additional costs would mean he’d need to pull $14 million from the ground to break even.

Furthermore, the two men discussed the price of oil’s volatility and its impact on the industry. In July 2014, the price of crude oil per barrel was more than $100. Three years later, it has been hovering around $50.

“Now I want you all to think a minute of your business that you’re in,” McDonald instructed media members. “What would happen if your revenue was cut 50 percent but your cost to operate didn’t drop significantly?”

I glanced awkwardly at the NewsOK reporters next to me and scrolled the inconsistent NonDoc balance sheet in my mind. Woof.

“Well, there’d be layoffs and bankruptcies in your business,” McDonald said. “That’s exactly what happened in our business.”

OIPA combats a changing narrative

In all, Monday’s OIPA media summit coupled with last week’s OEPA media dinner highlighted the precarious nature of oil and gas politics in Oklahoma.

Even Democrats draw campaign donations from the oil and gas world, and even media entities rely on the industry for potential advertising. When oil and gas companies are doing well in Oklahoma, everyone benefits. When their financial pictures darken, so do the state’s and job seekers’.

The question, then, becomes who will the public believe concerning the impact of gross production taxes and what will come of the discussion? A moderate increase? An incentive elimination for a flat 7 percent? Nothing at all?

At the moment, polling appears to show the public unhappy with the gross production tax incentive rate, but more efficient and effective messaging from the industry employees Wigley referenced could move the state’s narrative back to something everyone wants: jobs.

Even us in the media want those.