Although the numbers may be conservative owing to under-diagnosis and underreporting, medical researchers generally accept that at least 1.6 to 3.8 million sport-related concussions occur each year in the United States. With football season again in full swing and basketball and soccer on the horizon, it is worth revisiting the basics about the science behind sports-related concussions, their diagnosis and their management.

Beginning Tuesday, Oct. 15, NonDoc will publish a series of articles about issues surrounding traumatic brain injury (TBI) in amateur athletics. The information below is intended to offer a deeper scientific dive into TBI and its common sports colloquialism: a concussion.

What is a concussion?

In its most simple terms, concussion is an injury to the brain that causes temporary loss of normal neurological function. A concussion usually is categorized as a subset of mild traumatic brain injury. Although various descriptions of concussion exist, this simple definition addresses two key factors that all concussions generally share.

First, concussions are usually transient disruptions from which individuals should recover if given sufficient time for cognitive and physical rest. Second, concussions are associated with altered function — not necessarily structure — of the neurological system. That is to say, structural changes to the brain may or may not be observed. This may explain why 83 percent of patients presenting to the emergency department with documented concussion symptoms may have no structural abnormalities present on CT scan.

To address a common misconception about concussion, it’s important to realize that loss of consciousness is not required to make the diagnosis. Although a frank loss of consciousness may occur in a minority of cases, altered level of consciousness (somnolence or confusion) is common.

Concussion almost always results after acute trauma to the brain, such as an impact sport injury, an automobile accident or a fall. When structural cerebral injury is present after head impact, injuries may occur in a coup-countercoup fashion, in which effects of trauma are seen on both sides of the brain.

On a molecular level, biomechanical injury to neurons (cells) in the brain leads to the indiscriminate release of neurotransmitters and shifts in the distribution of electrically-charged molecules in the brain called ions. The brain, attempting to restore physiological balance, expends a great deal of energy during the post-concussive period. These molecular changes are thought to contribute to the post-concussive vulnerability and highlight the importance of cognitive and physical rest after suffering a concussion.

How are concussions diagnosed?

Clinically, the diagnosis of concussion spans multiple domains of signs and symptoms. Cognitive (feeling slow or having difficulty thinking clearly), physical (headache, nausea, vomiting), emotional (irritable or depressed), and sleep-related symptoms (sleeping more or less than usual) may be present.

Headache is the most commonly reported symptom, and some degree of amnesia (inability to remember events for a period before or after the event) may be present following a concussion.

A clinician’s best friend when diagnosing concussion is a thorough and complete history. No test is fully sensitive or specific in diagnosing or ruling out concussion, but history will almost invariably shed light on biomechanical trauma and a constellation of signs and symptoms from the list above.

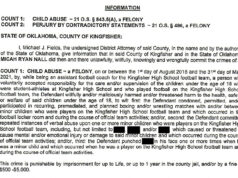

Diagnosis of concussion on the sidelines of an athletic field or soon after a big hit or head impact can be particularly challenging. Coaches and trainers may come under scrutiny for allowing players to return to the field without appropriately ruling out a concussion. While they cannot fully exclude concussion, aggregate diagnostic packages such as the third edition of the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT-3) may be useful for qualified professionals assessing for sports-related concussion.

More recently, ocular videography and other methods of tracking eye movements have been employed to evaluate players for concussion, but it should be noted that these tests do not definitively diagnose or rule out concussion.

How is concussion treated?

As complicated as the diagnosis of concussion is, its management and treatment are relatively straightforward. Physical and cognitive rest are the cornerstones of treatment of concussion. The overall goal of concussion management is to allow recovery of cognitive and physical function and to reduce the risk of second impact syndrome, a dangerous and potentially fatal sequela of repeat concussion before full recovery.

Serial examination by a physician to monitor the progression of signs and symptoms is useful. To that end, it is becoming standard practice for athletes in high school and college to receive baseline neurocognitive assessments to which post-injury assessments may be compared.

Although concussion and its treatment can be a challenging topic to wrap your head around, there are a growing number of good resources about concussion. Check out this TED-Ed video for a deeper dive.

More #concussion coverage

The hazy, frightening world of a sports concussion

Lacking data, Oklahoma high school concussion picture blurry