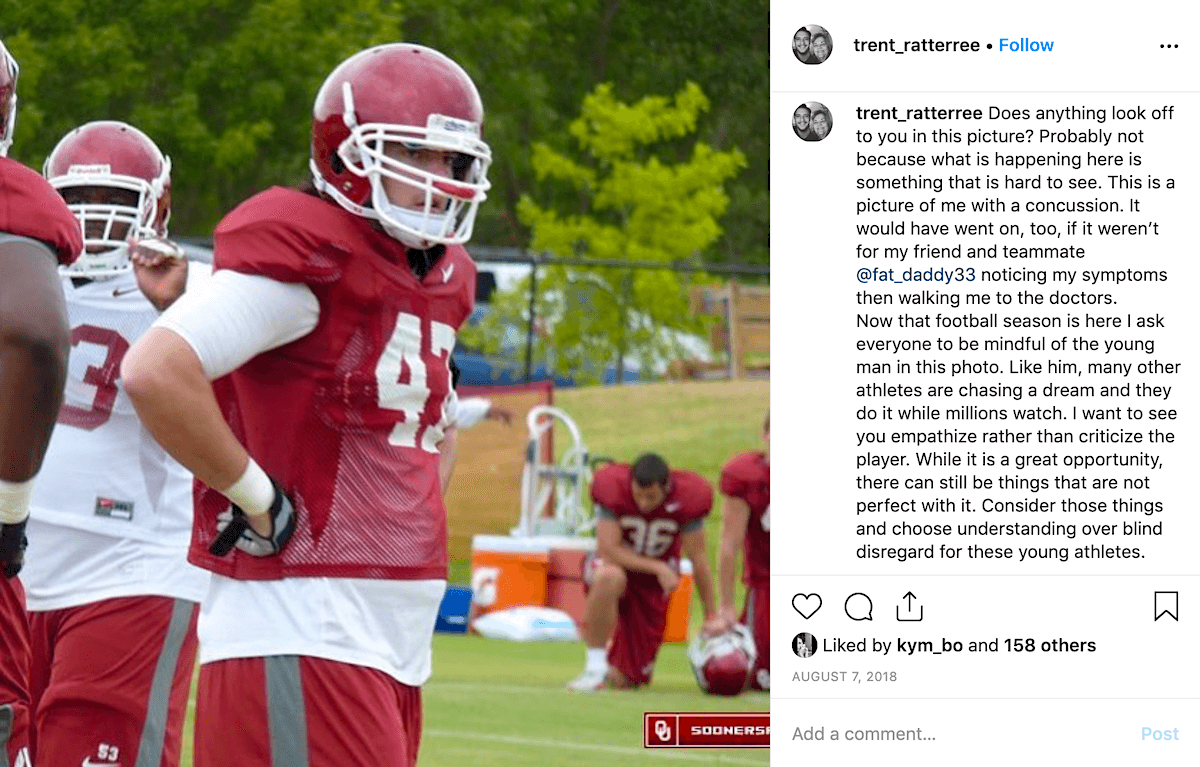

As Trent Ratterree wandered the University of Oklahoma campus in search of lunch, his belly growled but his mind felt scrambled thanks to a concussion he suffered over a series of pre-season practices days before.

By this time, the tight end from Weatherford had been in Norman for nearly five years. He knew every nook and cranny in his football orbit. The weight room. The indoor practice facility. Where the food was served. But not on this day. Everything was a hazy mess.

Ratterree eventually encountered a football coach who wanted to know what he was doing.

“I said I was heading to lunch, and I asked him where lunch was,” Ratterree recalls eight years later. “He told me I was two hours late and that I had missed it.”

That year, Ratterree joined an estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million high school, college and professional athletes who sustain sports-related concussions each year, according to the University of Pittsburgh Sports Medicine department. Of that total, about 300,000 play football.

Put simply, a concussion represents at least a mild traumatic brain injury, according Dr. Jaclyn Duvall, a neurologist in Tulsa who specializes in headache treatment.

“All that a concussion means is that there has been alteration in brain function from an external mechanical force,” Duvall said. “If someone has lost consciousness more than 30 minutes, that automatically puts them into the moderate category (of traumatic brain injury).”

The length of an individual’s alteration in consciousness is one differentiator between mild, moderate and severe traumatic brain injury, Duvall said. After a concussion, individuals may experience symptoms such as headache, confusion, nausea, sleep disturbance and light or sound sensitivity.

“I have some 16 and 17-year-olds who have sustained concussions, and they are pretty impaired from a headache standpoint that is limiting their school participation,” Duvall said. “It’s limiting their ability to function and sleep. They have emotional disturbance.”

Beyond short-term problems, sports-related head injuries can be debilitating in the long-term and potentially devastating at any time. In Oklahoma, a 16-year-old Southwest Covenant football player died after sustaining a head injury during a game in September, and a Lexington middle school player died during a game less than two weeks later.

Speaking generally, Duvall described an immediate and potentially deadly risk for athletes who have sustained a concussion: second-impact syndrome.

“The brain hasn’t had time to heal, so it’s in this hyper-stimulated state where (…) it’s basically just hyper-sensitive to any stress or second injury that might occur,” Duvall said. “That’s the initial thing that we think of where someone had a mild head injury, they went back out next week and they had another injury — whether it be mild or severe — and they ended up dying. That’s because of the delayed cerebral edema that can occur in that sensitive state.”

Ratterree’s symptoms were full spectrum. He had the headaches, the lack of concentration and the mood swings. One minute he was laughing hysterically, the next he was crying.

“Concussions can be frightening,” he said. “In my case, I don’t remember anything. That was my experience in college with my worst concussion. Before that, there were plenty of times where my bell was rung.”

Ruptured football helmet led to trouble

Ratterree doesn’t remember a specific blow to his head that caused his worst collegiate concussion. That’s probably because there wasn’t one. In his case, it happened slowly, blow after blow, thanks to a faulty helmet.

“Basically what happened was the air chambers in my helmet had ruptured, and I didn’t know,” he said.

The repeated impacts to his head during two-a-days yielded concussion. By then he had already overcome multiple injuries from the previous season, including a groin tear, just to get back on the field for the Sooners.

Even as he practiced, he wasn’t fully aware of what had happened to him. A teammate noticed something about Ratterree’s behavior wasn’t adding up.

“He asked me about a play, and I didn’t know the play, but I started explaining it and it turned out it was a completely different play,” Ratterree said. “We were running a sweep, and I was talking about a power. He took me to the team doctors, and within minutes they figured out something wasn’t right.”

One chilling effect from his concussion was an out-of-body experience.

“You’re feeling emotions that you know don’t make sense,” he said. “It’s an eerie feeling for your body to go through these emotions, and you feel detached from it. You feel a separation from your body and conscience. I could see my body crying and laughing, and I didn’t feel in control of it.”

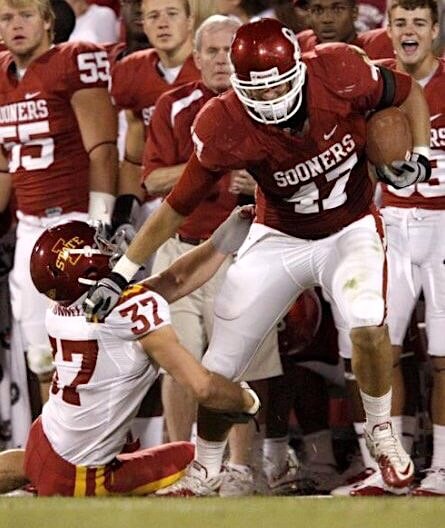

Ratterree eventually cleared OU’s concussion protocol and made it back for a truncated senior season. He scored a touchdown against Kansas State and another in the Sooners’ bowl game.

“I was able to turn it around,” he said.

But well after his football days ended, some unwanted remnants remain. Ratterree’s mementos from college include a diploma and headaches.

“Some of those concussion symptoms persist for a really long time,” Ratterree said. “To some extent, I still have them. I’ve always had migraines, but after playing college football they have been much worse. I get that aura and tunnel vision with some of them. I can almost be blind.”

Four concussions marred high school hoops career

To say John Paul Rischard’s sophomore year at Mount Saint Mary’s High School in Oklahoma City was tumultuous would be an understatement.

Rischard sustained three concussions playing for the school’s basketball team. The first came after he tripped and fell on the back of another player’s leg.

“I was out of school for a week,” he said. “When I came back, I had headaches. It was not a good time.”

Rischard didn’t play again for six weeks. During his first practice back, he took part in a drill where players dive for a loose ball. Another player landed on him and his head slammed into the court.

“That’s the one I remember most,” Rischard said. “I didn’t black out like I did with the first one, but I was really dizzy. I ended up on the couch in the coach’s office. I threw up both times.”

The third concussion came near the end of the season during a fast-break drill when a teammate’s elbow hit Rischard’s head.

“I think all three times I was just in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Rischard said.

Rischard’s fourth — and final — concussion came in October of his junior year when he once again took an elbow to the head.

“I missed the rest of the season,” he said. “I really didn’t know if I would want to play again.”

Rischard remembers shaking the first concussion off. He had seen his sister go through the same thing playing sports. The second and third knocked him off kilter for a while. His basketball career in ruins, his schoolwork suffered as well.

“I hated the headaches,” he said. “I was also falling behind in school. Having concussions and headaches and all of that makes it hard to concentrate on whatever it is you’re doing in school.”

Amazingly, Rischard decided to play his senior year. During practices, he didn’t take part in some drills with the hope that would reduce his risk of injury.

“I was fine all year,” he said. “I feel like I’m fortunate to not have any brain damage that I know of. I think I’m fine, and hopefully my friends and family would say the same.”

Hitting the old-fashioned way

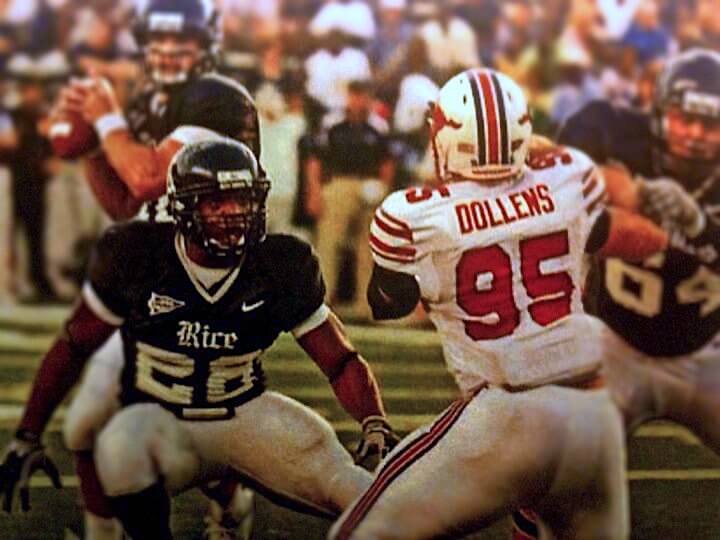

State Rep. Mickey Dollens (D-OKC) played football at Bartlesville High School so well that he earned a scholarship to Southern Methodist University. He capped his athletic career off as a member of the United States bobsled team.

Through it all, his head took a beating.

“There were times in high school where we would brag about how many gashes we had in the top of our helmet and how quickly we could destroy the top of a helmet,” Dollens said.

The abuse didn’t start there. Dollens began playing tackle football in seventh grade, later than many of his friends. But he remembers the relentless pounding of those early days, as high-impact practices were intended to make players tougher and less afraid of contact come gameday.

“We would hit each other so hard,” he said. “I’ve never been concussed or knocked out, but I have knocked out teammates and opposing team players.”

CTE: Dollens’ bobsled teammate died with brain disease

While football is the most violent sport Dollens played, it was his time training for the U.S. bobsled team that provided life-changing perspective when it comes to the damage head injuries can cause.

Like Dollens, bobsled teammate Zack Langston had a long history with football. He played in high school and at Division II Pittsburg State in Kansas.

“We had a lot in common,” Dollens said of Langston. “He had a good attitude and was a hard worker. He wanted to be the kind of person people depended on.”

While Dollens decided to give up bobsledding, Langston pressed on. Dollens still remembers the last time he saw his friend, selling him a Kevlar burn vest used to guard against ice abrasions.

“I was going to give it to him, but he insisted on paying for it,” Dollens said.

The two friends parted ways with Dollens telling Langston, “I know you’re going to make it.”

Six months later, in February 2014, Langston shot himself in the chest with a revolver. He left behind his longtime girlfriend and their 2-year-old son.

An autopsy revealed the 26-year-old’s brain had been affected by Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). The condition, which can only be diagnosed after death, has made news in recent years.

Junior Seau, Frank Gifford, Mike Webster, Aaron Hernandez and Ken Stabler are just a handful of former NFL players diagnosed with CTE following their deaths.

Seau and Webster took their own lives. In Seau’s case, he shot himself in the chest, preserving his brain for research just as Langston did two years later.

CTE symptoms include depression, aggression, memory loss and irritability, among others. It’s caused by repeated brain trauma, including but not limited to concussions. The Concussion Legacy Foundation notes repetitive subconcussive blows as a major risk factor for CTE, which causes progressive degeneration of brain tissue.

“For that disease to get the best of him makes us all scared,” Dollens said of Langston. “It makes us all very cautious not to underestimate the impact of a brain disease like that.”

While Dollens can’t recall an instance where he suffered a concussion, he sometimes wonders if he is at risk for CTE.

“Whenever you’re feeling a little off,” Dollens said, “you have to wonder, ‘Is this early onset of CTE or is this just normal emotions?'”

When the fog clears

Today, Ratterree works for U.S. Rep. Kendra Horn (D-OK5). While he said football opened a lot of doors for him in life, he sometimes finds himself wondering if he is at risk for CTE. He also worries about his former Weatherford and OU teammates.

“To us, it’s always on our minds because we know first hand,” Ratterree said. “We’ve seen guys who have had other mental health issues like depression, and they seem fine until something happens. We check in on each other. We have a pretty strong community.”

Today, Rischard is a 21-year-old student at Creighton University in Nebraska. He still plays basketball, but only in pick up games.

“And even then I don’t play hard,” he said. “It’s just for fun.”

Rischard’s restrained effort on the court is a product of his four concussions, but despite the experience he has few long-term fears of brain injury or CTE.

“I’m not too worried about it,” he said. “In the back of my head, I know I can’t afford to get another concussion. I just try to be as careful as I can.”

These days, Ratterree doesn’t lament the end of his football career. He had a few training camp invites after college, but by that time he had already shed more than 40 pounds.

“Today, I can say I got plenty out of football,” he said. “I’m not sad that I didn’t play in the NFL, but it’s taken some time to get to that place.”

‘He’s always had head injuries’

Duvall, the neurologist who has recently opened a headache practice at Tulsa’s Utica Park Clinic, has treated former NFL players who “are in bad shape.”

“They can’t work because they can’t focus on a task long enough to complete work. Their migraines are so disabling they can’t go out in the sunlight,” Duvall said. “They are kind of excluded to the house trying to avoid any movement because it will make them sick and nauseous.”

Duvall referenced one particular player who sticks out in her mind.

RELATED

Understanding the science of sports-related concussions by Dr. Ashiq Zaman

“He is in his mid-30s. And he kind of tells me, ‘Yeah, I’ve had head injuries my entire life.’ But he couldn’t pick out just one time that he was unconscious for 30 minutes to meet a moderate TBI. It’s just that he’s always had head injuries,” she said. “This guy is disabled. He has post-traumatic headache, which is migraine. And all of his symptoms cumulatively have made it really challenging for him to function. He is struggling in his marriage with his children because he suffers from this mood lability where he goes back and forth between feeling good and suddenly being irritable or crying at the drop of a hat.”

For his part, Ratterree does not have kids yet. But if he does have a son who wants to play football, he won’t stand in the way, even with what he’s been through.

“If I had a son or daughter that wanted to play, I wouldn’t discourage it,” Ratterree said. “I think they need to try it. But I would make sure they know what they’re getting themselves into.”

Dollens, who has a 1-year-old son, said he and his wife, Taylor, have already discussed the topic.

“We know that we are fine having our son, Dean, play flag football, but we’re still kind of on the fence about tackle football and what that looks like 10 years from now,” Dollens said.