The Osage Reservation was disestablished and the state of Oklahoma retains criminal jurisdiction over crimes committed by tribal citizens in Osage County, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ruled today.

The state court decision references and aligns with the 2010 U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Osage Nation v. Irby, which determined that the tribe’s reservation was disestablished despite Congress not taking specific action to do so. Complicating public understanding of the situation, the Osage Nation retains minerals rights within its territory and is often colloquially referred to as having an underground reservation.

Thursday’s 32-page decision in McCauley v. State comes on the heels of national media attention brought by Martin Scorsese’s film Killers of the Flower Moon. The film depicts the most infamous of the 20th century Osage murders, many of which remain unsolved.

Relying on federal court’s decision in Osage Nation v. Irby, Oklahoma’s highest criminal court declined to issue a ruling incongruent with the 10th Circuit.

“The 10th Circuit’s decision in Osage Nation applies here because of its preclusive effect,” wrote Vice Presiding Judge Robert Hudson for a unanimous court. “Appellant’s claim is entirely derivative of the Osage Nation’s original claim, and as such cannot be relitigated here by appellant.”

The decision keeps federal and state law consistent on their approach to the Osage Reservation. In 2010 Osage Nation v. Irby, the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals found that the Osage Reservation had been implicitly disestablished.

However, the Irby decision came before the U.S. Supreme Court found the Muscogee Nation Reservation was never disestablished in the historic 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma decision, which functionally affirmed the eastern half of Oklahoma as a series of Indian Country reservations. The Irby decision also used a 1984 legal test for determining whether a reservation had been disestablished. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in McGirt relied on a different standard and only focused on whether Congress had disestablished the Muscogee Reservation.

Prior to the McGirt decision, courts would look to the 1984 Solem v. Bartlett decision to determine when a reservation was disestablished. Under a Solem analysis, courts looked at acts of Congress, the circumstance around the passage of acts relating to a tribe, and subsequent events after the passage of the act.

The Solem test made it easier for courts to declare reservations disestablished because it allowed them to consider factors such as demographic changes within a historic reservation when determining disestablishment. McGirt narrowed the Solem test to a textual inquiry that only examines the words passed through Congress.

Notably, the 10th Circuit in Irby found “the operative language of the statute does not unambiguously suggest diminishment or disestablishment of the Osage Reservation” before ruling the latter two Solem factors weighed in favor of disestablishment. Simply put, Irby’s analysis and holding appear incompatible with the McGirt decision.

In a specially concurring opinion in the new McCauley decision, Court of Criminal Appeals Presiding Judge Scott Rowland defended the applicability of the Solem test by pointing out that the McGirt decision never explicitly overruled Solem and that it’s not a state court’s place to overturn federal precedent.

“The majority opinion (in McGirt v. Oklahoma) mentions or cites approvingly the Solem case about a dozen times, and nowhere indicates its abrogation, deprecation or overruling,” Rowland wrote. “If McCauley is correct that McGirt does violence to the Solem analysis that cases such as Osage Nation (v. Irby) should no longer be followed, that pronouncement must come from the federal courts.”

Thursday’s decision from the Court of Criminal Appeals forecloses efforts for the Osage Nation to seek recognition of its reservation through state courts. If the nation continues to push for the recognition of its reservation, it would have to support a case in federal court and see if the 10th Circuit will reverse Irby in light of McGirt.

Jury watching also brought up in McCauley appeal

Dakoda Aaron McCauley was convicted in October 2021 by an Osage County jury of heat of passion manslaughter and sentenced to 22 years in state prison. McCauley was convicted of killing Frankie Cotto in May 2018 in McCauley’s kitchen after Cotto had an affair with his partner.

McCauley’s attorneys challenged his conviction on more grounds than simply the Osage Reservation claim.

During jury deliberations, which are supposed to remain secret, a few court employees watched jurors in the courtroom on a security camera. A similar incident in Rogers County 2022 left assistant district attorneys Isaac Shields and George Gibbs facing disciplinary actions that are still pending before the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

Unlike the Rogers County case, prosecutors only briefly viewed the footage with Assistant District Attorney Brett Mize admitting that he “glanced at it for 30 seconds” on his way to the restroom.

However, the appellate court was ultimately unconvinced by McCauley’s argument and found the error did not constitute a violation of McCauley’s constitutional rights.

“There is no indication in the record that the jury was aware of the camera’s presence in the courtroom at the time of their deliberations, and thus its presence could not have ‘exerted a chilling effect on the jurors,'” wrote Hudson. “Our review of the security video confirms that it provided no useful knowledge about the deliberations to a viewer, particularly because of the lack of audio.”

However, the court noted that viewing ongoing jury deliberations is still a criminal offense in Oklahoma.

Another jury issue presented by McCauley’s attorneys on appeal involved a juror taking a short phone call before jury deliberations. According to court documents, one juror talked on their phone with an unknown party before deliberations began, and two others texted before deliberations.

Jurors are not supposed to communicate with outside parties during jury deliberations in order to prevent outside influence from swaying the jury’s opinion.

The Court of Criminal Appeals rejected this claim because defense counsel failed to object to the jury’s “short break” on the record during trial.

“No objection was made when the jurors were allowed to separate, and no admonishment was requested,” wrote Hudson. “There was thus no error, plain or otherwise, from the segment of the security footage which shows the jurors on a short break, before the commencement of their deliberations, while the courtroom was being cleared.”

McCauley’s attorneys also argued that Associate District Judge Burl Estes briefly talking with a juror as he walked through the courtroom with papers and a cup of coffee interfered with the jury deliberations. The Court of Criminal Appeals found the judge’s conduct was not an appealable error.

“The video shows that the judge’s communications with the jurors were made in passing, lasted a few seconds and occurred while he was clearing out of the courtroom prior to the commencement of deliberations,” Hudson wrote. “There was thus no actual or obvious error from the trial court’s brief communications with the juror during the break, prior to the commencement of jury deliberations.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

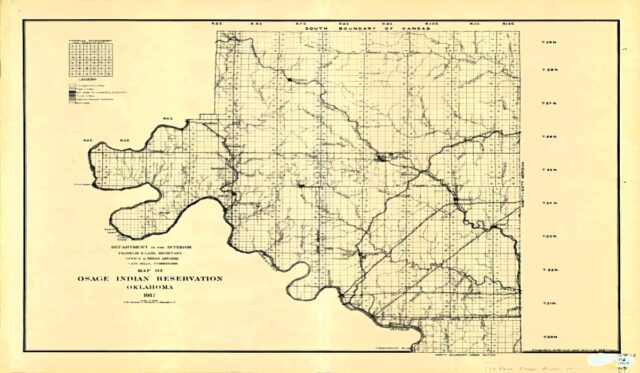

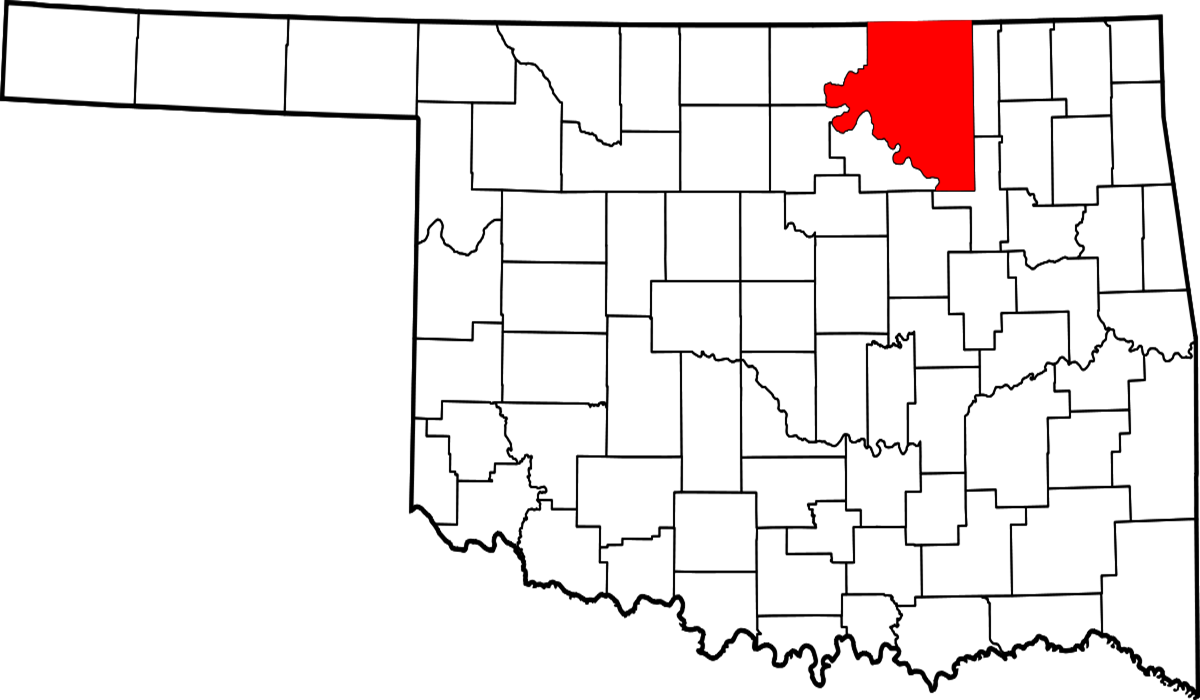

The Osage Nation’s road to Osage County

Previously centered around present-day Missouri, but including parts of present-day Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas, the Osage Nation was historically one of the dominant powers in the Plains region around the time of the founding of the United States. Before the United States expanded west, the French and Spanish were the dominant colonial powers in the region, and Jesuit missionaries heavily influenced the nation.

As the United States expanded west, the Osage people were removed to Kansas and then were removed again to their present-day territory in what is now Osage County after the Civil War. The current Osage Nation was carved out of the Cherokee Nation Reservation, which was previously Osage territory before Cherokee removal.

The Osage Nation was part of Indian Territory until the creation of Oklahoma Territory in 1890. Osage County, the largest county in Oklahoma, was required to include the entire Osage Nation when Oklahoma became a state in 1907.

At the end of the 19th century, the discovery of oil brought an economic boom to Osage County that lasted until the Great Depression and spurred the immigration of settlers, an increase in crime and a substantial rise in the wealth of the Osage people. The era, sometimes known as the Reign of Terror, is depicted in Killers of the Flower Moon as well as in the work of Osage writer John Joseph Mathews, especially his 1934 novel Sundown.