Intentional grounding. Five-yard penalty from the spot of the foul. Loss of down.

Those are 14 words that no quarterback, coach or high school football fan wants to hear when their team has the ball. Generally speaking, such a penalty is called when a quarterback drops back to pass, gets pressured by the defense and throws the ball away without directing it near an eligible receiver.

In college, professional and even Texas high school football, a quarterback can avoid intentional grounding — and big hits from oncoming defensive players — by doing two things: First, running left or right beyond the “tackle box” boundary of his offensive line; second, throwing the ball anywhere beyond the line of scrimmage, even out of bounds.

But in the National Federation of State High School Associations rulebook, no such exemption for intentional grounding — or an illegal forward pass — exists.

The NFHS rulebook is used by the Oklahoma Secondary School Activities Association, leaving high school quarterbacks under heavy duress with a bevy of negative options: lose yards by sack, slide, run out of bounds or run back toward the line of scrimmage to save yardage, despite the risk of absorbing hits from oncoming defenders.

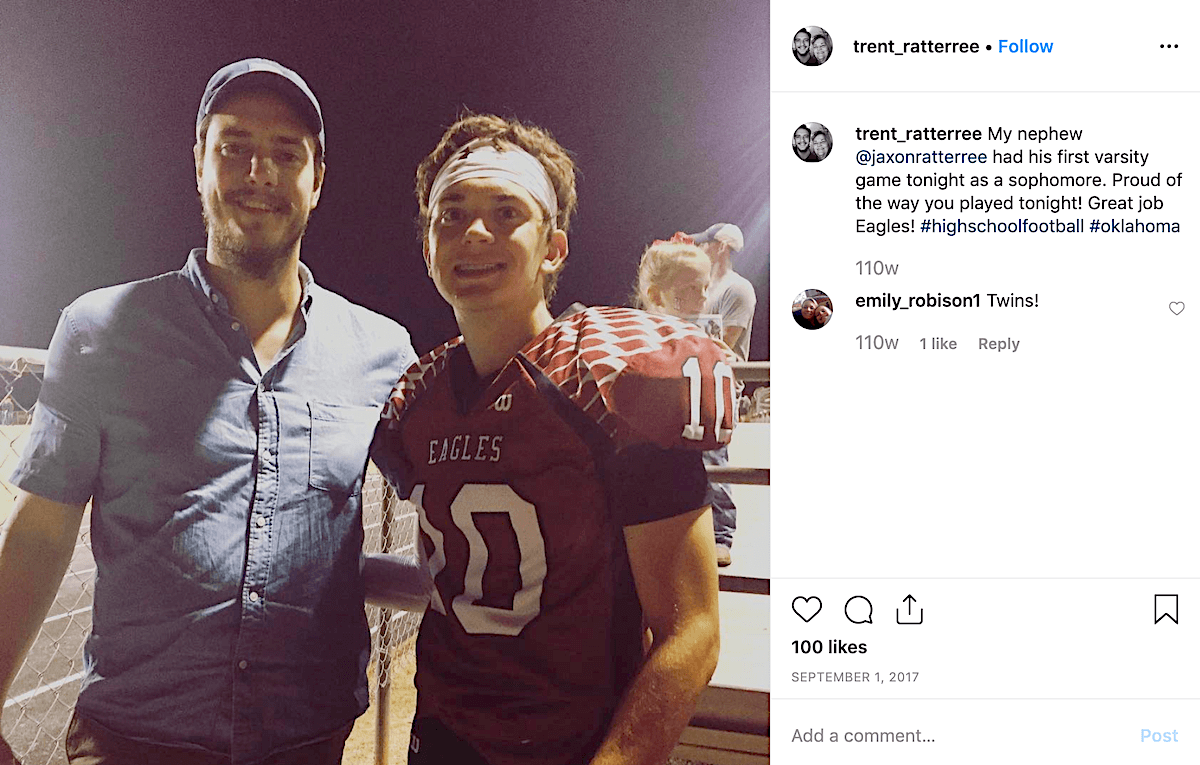

“I think the intent of the rule is to keep the game moving and reduce the amount of field time out there,” said Weatherford High School graduate and former OU football player Trent Ratterree. “I think it has a good-faith intention, but the way it works out puts the quarterback in danger and in threat of a concussion.”

Ratterree would know.

In 2017, he watched his nephew, Jaxon, sustain a concussion on a play where he might have chosen to toss the ball out of bounds, had such an exemption from intentional grounding existed in Oklahoma high school football.

“I don’t remember much about it, but I’ve watched film,” Jaxon Ratterree said. “Basically, I was going to drop back for a pass and they brought a blitz on. So one came free. I scrambled and was running to my left. (…) There really wasn’t [any receiver] coming back, so I was just going to take off running with it. But I was going and running and a dude kind of stood me up, and I was kind of trying to break away from his tackle.

“As I was going down, two guys came and hit me on both sides of the head at the same time, and I was out cold.”

While Jaxson Ratterree does not know how he would have handled that play if Oklahoma’s high school rules had allowed him to throw the ball away, he “definitely” believes coaches and OSSAA administrators should consider adding such an exemption to the intentional grounding rule.

“I think if there was a rule kind of like the college or NFL rule where as long as you are outside the tackle box you can throw it away, I think there would probably be a lot of different outcomes,” the 17-year-old senior team captain said. “I think quarterbacks would probably use it more.”

While he prides himself on being a mobile quarterback who has the ability to escape pressure and make plays, Jaxon Ratterree also knows many of his peers have less of that skill set.

“I’m lucky with being able to run,” he said. “But there are probably a ton more (guys) who — if they had the luxury to throw it out of bounds and not get a penalty called on them — they would probably use it.”

He also knows that, just as he is a key piece of Weatherford’s offense, other quarterbacks are extremely valuable to their teams. Having quarterbacks take unnecessary hits that risk injury can jeopardize entire seasons, he said.

“I definitely think it should be talked about, because I feel like most concussions that quarterbacks get aren’t from a designed run or a mega-hit,” Jaxon Ratterree said. “It’s more of when the pocket breaks down, they scramble and don’t know what to do with it, and the next thing they know three guys come and hit them.”

‘I kept asking what had happened to that dog’

When Jaxon Ratterree sustained his concussion midway through the third quarter of a 2017 game, he lost a chunk of his memory about what had happened earlier.

“I can’t really remember anything but the first quarter,” he said. “From what I was told, I knew who my mom and my dad were, and I knew who my coach was. And I remembered a dog who had died when I was 4. I kept asking what had happened to that dog.”

He said he did not know who his sister was for 30 to 45 minutes.

“It was scary to think about,” Ratterree said. “You do something for an hour and a half and you have no memory of doing any of it.”

Weatherford High School has an athletic trainer and a physician at its games, Ratterree said, so he was checked at the stadium and told he did not need to go to the hospital. Instead, he was checked on at home every two hours.

“Saturday and Sunday I spent most of my time in bed with every light off either sleeping or staring at the ceiling,” Ratterree said.

He missed school Monday but returned Tuesday despite light sensitivity. He sat out his team’s next game on Friday, returned to practice the following Tuesday and played in the subsequent Friday’s game.

“I didn’t do anything running or physical for about a week or nine days,” he recalled. “I didn’t do anything school-related for about four or five.”

Ratterree, who has a chance to play either baseball or football at the next level, said he had a new emphasis on trying to avoid big hits when he returned to the field.

“It was a boneheaded play, and I probably shouldn’t have done it. I was running and didn’t really have anyone in the area, so I was trying to get out of bounds, but I couldn’t,” he said. “I definitely had to think about smarter ways of (realizing) what hits I can take and what hits I can’t.”

OSSAA: Coaches can submit rule changes for national proposal

OSSAA executive director David Jackson played quarterback in high school at Pauls Valley and later coached at the school as well. He knows the traumatic brain injury risks associated with football, and he spoke with NonDoc about the topic in a previously scheduled interview the day after Southwest Covenant player Peter Webb died from a head injury.

“From what I understand of what happened here, it was one of those scenarios that shows playing football comes with inherent risk no matter what you do,” Jackson said. “Your heart just goes out to the family.”

Southwest Covenant headmaster Steve Lessman did not return calls seeking comment about the tragic event, but he did release a statement reported by The Oklahoman on Sept. 16.

“Peter is gone from this earth, yet the miracle of the gospel is more true for him now than ever,” Lessman said in the statement. “He is with the Lord. Please pray for the Webb family and may we wrap our arms around them in the coming days, months, and years. We know our students are struggling in a big way.”

Jackson called the situation “so unfortunate.”

“The equipment is probably as good as it’s ever been,” he said. “The rules are implemented in a way that probably makes the game have reduced risk as much as it has ever been.”

But Jaxon Ratterree and Trent Ratterree believe the OSSAA should look at the intentional grounding rule and consider adding an exemption like college and NFL rulebooks have.

Rep. Mickey Dollens (D-OKC) agrees with the Ratterrees that high school quarterbacks should be protected with the same rule designed to protect collegiate and professional players.

“There definitely should be an exemption. It doesn’t detract from the entertainment value of the game, in my perspective,” Dollens said. “If you don’t have someone open downfield, throw it out (of bounds) and try again. I don’t want to see someone get unnecessarily clobbered because they’re trying to win for their team.”

A former defensive lineman from Bartlesville who played at Southern Methodist University, Dollens knows about clobbering quarterbacks.

“Their mind is, ‘Win at all cost.’ That’s the mentality they’re going to have,” he said. “That quarterback who is looking to play at the next level and is wanting to make something happen, they won’t step out of bounds. They’ll have to be hit and taken out of bounds. That’s going to cause more issues and problems with head injuries.”

Jackson, the OSSAA director, is unsure whether adding an exemption for intentional grounding would help with quarterback safety.

RELATED

Lacking data, Oklahoma high school concussion picture blurry by Tres Savage

“The high school rules-writing committee in football at the federation is as good as it comes. Football is the only [sport] that uses a representative from every single state that is a member of the federation,” said Jackson, who served as NFHS president for the 2018-2019 academic year. “Because sports medicine is so involved in that committee, if there was a thought that there was a safety factor involved in that particular rule, they would be all over it. I would feel safe to say that they would have already implemented that rule that college and NFL has.”

Jackson said that if any Oklahoma high school football coach thinks a rule should be considered for adjustment, they can submit it for OSSAA to propose at the national level.

“If any of our member-school football people think that is a rule change that needs to be looked at, then we will submit it as a proposal for the rules-writing people to take a look at,” he said.

He also harkened back to his days on the field.

“Being a former quarterback, I always thought that if I was in that situation, I’m going to throw it away anyway,” Jackson said. “I’m going to take my chances that maybe I’m throwing near a receiver instead of taking a sack. We didn’t want to lose yardage if we didn’t have to.”

Referee: ‘It should be like it is in college and the pros’

OSSAA-sanctioned referee Jason Deberry has worked high school football games for eight years and tries to be vigilant about pulling student athletes from games when they exhibit symptoms of a concussion.

“Once every few games, we will have a kid ‘get his bell rung,’ and as an official I will kill the play and send the kid off,” Deberry said. “A lot of times the kid will say, ‘No, no, I’m OK.'”

Other times, such as in Jaxon Ratterree’s experience, players lose consciousness after particularly vicious blows. Deberry said plays where quarterbacks are scrambling with nowhere to throw the ball present some of the game’s most dangerous situations, be they blind-side blocks or hits to quarterbacks who have nowhere to throw the ball.

“Those type of plays where you have a (snapped) ball going over a quarterback’s head, that’s where you have guys getting blown up. That’s where the crazy stuff happens,” Deberry said.

As a result, Deberry believes high school quarterbacks should be allowed to throw the ball away to avoid big hits.

“Personally, I think it should be like it is in college and the pros,” he said. “If it gets back to the line of scrimmage and they are out of the tackle box, yes, I think the high school rule should emulate college.”

Deberry referenced how Texas plays by a variation of college rules, and he called the NFHS intentional grounding rule “a little antiquated.” He said it causes “big confusion” even among players and high school coaches.

“We hear every year from coaches, ‘Well he was outside the tackle box.’ We hear that almost weekly when that happens,” Deberry said. “And we say, ‘Coach, we don’t have a tackle box.’ They’re confused because universally people watch the NFL and NCAA.”

Deberry said the lack of intentional grounding exemption in high school puts players at greater risk and puts officials in a difficult spot making judgment calls about the location of receivers.

“We’re getting screamed at because coaches and fans don’t realize we don’t have all of those other requirements,” he said.

‘This probably happens a lot everywhere’

For Trent Ratterree, the opportunity to tweak the NFHS intentional grounding rule for player safety hits close to home.

“This happened to my nephew. He could have thrown it away, but he ended up running down the field and got hit and knocked out,” Trent Ratterree said. “That’s when this started clicking for me. I wondered why he didn’t throw it away, and I was informed there was a rule where you can’t throw it away in Oklahoma high school football.

“This probably happens a lot everywhere.”

RELATED

Revisiting the science of sports-related concussions by Dr. Ashiq Zaman

The older Ratterree, who sustained his own frightening concussion while playing at OU, said OSSAA administrators should consider the dynamics between kids and their coaches.

“The way that the consciousness of high school football works is if you run out of bounds and take a 10-yard loss, you’re going to hear about it. There’s going to be criticism,” Trent Ratterree said. “So instead of taking that loss, the kid is going to push himself forward and take a hit. They can’t just lob it out of bounds.”

He said Oklahoma’s intentional grounding rule needs an exemption.

“You could step out of bounds, you could slide, you could take a knee, but anyone who played high school football can think back and put themselves in the perspective of what your coach would have said to you if you just went out of bounds,” he said. “I think with a rule change, coaches would be more likely to say, ‘Just toss it out of bounds and we’ll live to play another play.'”