This year saw one of the costliest Atlantic hurricane seasons — both in dollars and lives — since accurate records of them were first kept in 1851.

With a total of eight hurricanes so far — five of which are classified by the National Hurricane Center as “major hurricanes” (Category 3 or higher) — the cost of damages is estimated by Time magazine to be more than $200 billion. That does not even mention the hundreds of fatalities, and we are only one third of the way through hurricane season.

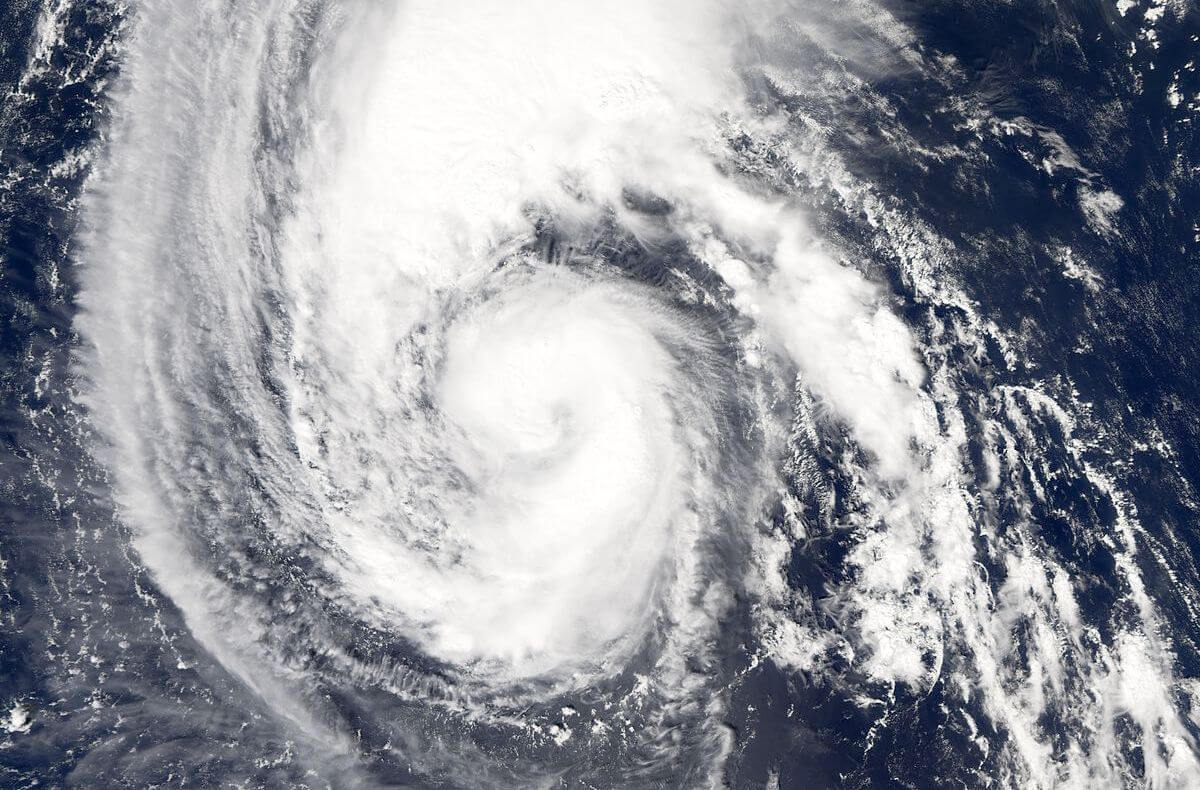

As a result of this, let’s take an in-depth look at the formation, causes, features and damages of Atlantic hurricanes, which are among the most powerful storms on Earth.

From the other side of the planet

To do this, of course, we must start at the beginning of these monster storms, nearly half a world away: among the monsoons of South East Asia.

According to Russel Schneider director of the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center, these storms start out as disturbances in the upper atmosphere of particularly low air pressure.

“[The disturbance] propagates usually westward within the tropics across the Sahara, creating dust storms in North Africa,” Schneider said by phone. “As it moves off the coast and goes out over the warm ocean water it organizes the thunderstorms from just being random thunderstorms to being concentrated in one location.”

RELATED

Riding out a hurricane with ‘no idea what’s going on’ by William W. Savage III

When the thunderstorms begin to coalesce, the Coriolis effect causes them to start rotating counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere. As they intensify, the rotation prompts the formation of the classic eye structure at the center. The energy stored in warm water below the burgeoning storms will feed them, intensifying both the winds and the rotation.

This, Schneider said, is the first step in the quick development of large rotating storms, and it is a hallmark of Atlantic hurricanes. It equates to a positive feedback loop between the warm ocean water, the thunderstorms below the low-pressure area, and that area itself which, according to Schneider, “is a runaway spiral” facilitating fast-paced and large-scale intensification.

“If the thunderstorms persist, you’re going to develop a low-pressure area that becomes more and more intense,” Schneider said.

Hurricane Harvey, the first major hurricane to make landfall in the United States since 2005, grew from a sub-hurricane tropical depression into a full-blown Category 4 hurricane in just under two and a half days.

Schneider compared being in the most intense part of a storm like Harvey (the Eyewall, surrounding the eye) to being in the middle of moderately weak tornado (EF 2 or EF 3) for upwards of six hours.

However, according to Schneider, the winds are not the worst part of a hurricane. Instead, it is what those winds bring with them.

“As they move across the ocean,” Schneider said, “the winds actually push water ahead of them, resulting in surges of water. Storm tides, in a sense.”

This phenomenon, called a storm surge, is the most devastating part of a hurricane.

Schneider explained that as it approaches bays and inlets near the coast, the storm surge concentrates in coastal areas, particularly where the water would naturally converge to form higher tides.

“It’s in some ways similar to a tsunami,” Schneider said. “The surges can reach as high as 25 feet and (it) is a sustained surge of water.”

‘It’s not that the levees were toppled’

Back in 2005, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, the main factor in that devastation was the storm surge.

“It’s not that the levees were topped,” Schneider said. “When the storm surge swept into Lake Pontchartrain, the pressure of the 15-foot increase in water level overwhelmed the already saturated earthen levees, causing catastrophic flooding similar to what Texas witnessed during Hurricane Harvey.”

What has been especially difficult about the 2017 hurricanes is their close chronological proximity to one another. It’s not unusual for storms to form in quick succession, Schneider said, but it is rare for three such storms to all make landfall in the United states as Category 3 or higher. It is, he said, the first year that such an occurrence has been recorded in which all three storms were Category 4 or higher.

He said people often have misconceptions about the power of the storms, that is, until one hits them square on.

“We tend to calibrate relative to what we’ve already seen and with hurricanes this goes toward people who get minor damage from what was considered a category storm,” Schneider said. “They actually weren’t in the Category 5 part of the storm, but they’ll say ‘well I lived through a category five and we were fine.'”

Having this mindset can be detrimental to evacuation efforts ahead of a hurricane making landfall, Schneider said.

“There is also a tendency that if they evacuate and don’t get hit, they think it was a waste of time,” he said.

With greater access to high tech forecasting tools, however, meteorologists are getting better at predicting the intensity and path of these storms while being better able to warn citizens and businesses of the impending danger.

A key part of this effort, according to Schneider, isn’t necessarily getting the information to people so much as getting them to heed it.

“That’s where our interaction with social scientists has been growing as we’ve gotten better at describing these things,” Schneider said.