As state and tribal leaders await potential congressional action about jurisdictional issues raised in last month’s McGirt v. Oklahoma decision, state Attorney General Mike Hunter is tracking nearly 200 new appeals of state criminal convictions and is hoping a potential wave of civil court challenges can be avoided in eastern Oklahoma.

“I believe it is an axiom that when there is uncertainty with regard to commerce and economic development, that’s not good for anybody,” Hunter said at a press conference this afternoon. “It’s our position that the civil implications of McGirt are going to be the subject of litigation that could have a checkerboard sort of consequence over time. Our view is that it is better to have certainty and to have jurisdictional issues resolved via Congress as opposed to individuals trying to expand McGirt’s application or somehow argue that it has application beyond the Major Crimes Act.”

Owing to the July 9 U.S. Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma — which affirmed that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s historic reservation had never been dissolved — criminal jurisdiction concerning tribal citizens under the Major Crimes Act now lies with tribal courts and the federal government across most of eastern Oklahoma.

Hunter called his press conference to publicize his pledge “to challenge every single appeal that attempts to overturn longstanding convictions on historic tribal land,” but he also answered questions about what could happen if legal challenges regarding taxation, environmental issues and other regulations are filed before Congress takes any action.

“There’s really no reservation like this in the country where you have Indians and non-Indians basically inculcated, doing business with each other, living across the street from each other in a way that we have existed for 113 years,” Hunter said.

Deal or ‘cooling off period’?

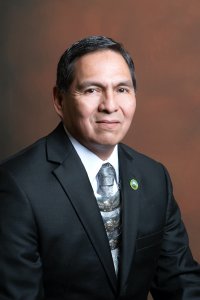

One week after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Jimcy McGirt — who had been convicted of child sex crimes in Wagoner County District Court — Hunter announced an “agreement in principle” with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and the four other tribes whose historic reservations appeared to be affirmed in the decision. But within days, Seminole Nation Chief Greg Chilcoat and Creek Nation Principal Chief David Hill announced they were not in support of the purported agreement and wanted additional guarantees that their sovereignty would withstand any congressional action.

“The Seminole Nation has not formally approved the agreement-in-principle announced by the other four tribes,” Chilcoat said. “To be clear, the Seminole Nation has not been involved with discussions regarding proposed legislation between the other four tribes and the state of Oklahoma. Furthermore, the Seminole Nation has not engaged in any such discussions with the state of Oklahoma, including with the attorney general, to develop a framework for clarifying respective jurisdictions and to ensure collaboration among tribal, state and federal authorities regarding the administration of justice across Seminole Nation lands.”

Hunter, however, said Monday that he has been in discussions with the Five Tribes for about two years and that talks have entered “a cooling off period.”

“I wouldn’t say the agreement has fallen through. We definitely had some setbacks with regard to people withdrawing from the discussions,” Hunter said. “I don’t want this to become an us vs. them thing. That’s been my position since the beginning.”

Any congressional action taken could focus on simply establishing clearer criminal jurisdiction in eastern Oklahoma, but it could also officially disestablish the Five Tribes’ reservations and make other sweeping changes.

In his public statements after the McGirt decision, Hill has emphasized the importance of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation to his tribe and its citizens. As a result, he currently opposes any congressional effort to terminate the reservation.

“Whatever the motivation to undo the decision and disestablish our reservation, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation will not sit down,” Hill wrote in a commentary published by the Tulsa World. “The Supreme Court’s affirmation is not a problem to fix, but rather an opportunity to flourish.”

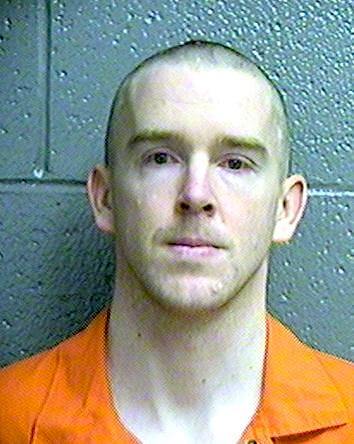

‘Shaun Bosse never deserves to get out of prison’

In discussing the complex situation Monday, Hunter highlighted one man he hopes will perish instead of flourish: Shaun Bosse, a white man convicted of killing Chickasaw Nation citizen Katrina Griffin and her two children in 2010.

“One thing I think we can all agree on is that this was a horrific crime. It is also an example of how important it is for the state to seek justice on behalf of Indian victims who were abused, victimized and killed by non-Indians,” Hunter said. “Shaun Bosse never deserves to get out of prison. He deserves to stay in McAlester on death row until he is executed.”

Hunter said Bosse’s lawyers have filed a challenge arguing that “because his victims were Chickasaw Indians — Native Americans — and the crime occurred on historic Chickasaw lands, the state did not have jurisdiction to prosecute him for the murder of a mother and two children.”

Hunter filed a legal brief Monday with the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals opposing Bosse’s challenge, which the attorney general said serves as an example that “the problems the McGirt case presents are not theoretical.”

“We are not going to allow our justice system to be exploited by individuals who have murdered, raped or committed another crime of a serious nature while the federal government considers whether to re-arrest or adjudicate their cases,” Hunter said.

The ACLU of Oklahoma quickly criticized Hunter’s statements.

“McGirt v. Oklahoma is the catalyst for addressing a long history of broken and ignored promises by the State of Oklahoma and its criminal court system. It is not the cause of confusion, as [Attorney General] Hunter classified it in his latest attempt to circumvent tribal sovereignty,” said Nicole McAfee, director of advocacy and policy for the ACLU of Oklahoma. “Mr. Hunter made several concerning statements, suggesting everything from Oklahoma courts having concurrent jurisdiction with the federal government over alleged crimes on reservation land with Indigenous victims to the idea that courts, not tribes, get a say on who is Indigenous. The statement by Mr. Hunter that the state has a responsibility to protect Indigenous victims is laughable given the lack of attention to the significant number of Indigenous women missing and murdered every year.”

Hunter said his office has identified between 1,500 and 2,000 criminal convictions “who I guess we would say could argue that McGirt applies.”

“It’s definitely going to represent a burden on our office and district attorneys,” Hunter said.

Hill: ‘Greater prosperity and safety for all’

As Hunter tries to mitigate that burden by pushing for congressional action clarifying jurisdictions, state, federal and tribal leaders have quite the needle to thread: ensuring prosecutorial punishment for violent criminals while negotiating for some level of civil-law certainty with tribes that have a rare opportunity for their citizens and their economic interests.

“As the only tribal nation whose lands were directly at issue in the Supreme Court case, we are mindful of our responsibility to play a primary leadership role in ensuring that the Court’s decision results in greater prosperity and safety for all,” Hill said in a July 29 statement.

Because the Seminole Nation, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation and Choctaw Nation each have separate treaties with the U.S. government, Hunter said “a court needs to make a decision” about whether the McGirt decision applies to all of them as well. While that would seem to be the prevailing presumption among all parties, those four tribes’ reservations have not been officially affirmed like the Creek Nation’s has.

That fact further complicates the ongoing negotiations with the tribes, which have also found themselves in a legal dispute with Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt over the state Model Tribal Gaming Compact for the past year. A federal judge ruled last week that the compact automatically renewed for another 15 years owing to action taken by the Oklahoma Horse Racing Commission. Asked Monday if the dispute between Stitt and the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee and Creek nations had complicated his two years of negotiations over the potential McGirt decision, Hunter paused and looked at the ceiling.

“It’s been a distraction,” Hunter said.

Choctaw Nation general counsel is Hunter’s opioid co-counsel

To that end, Hunter — who was first appointed as attorney general by Gov. Mary Fallin in 2017 and elected to a four-year term in 2018 — has faced a full plate for the past three years. Beyond McGirt and the gaming compact dispute, Hunter has toiled with high-profile lawsuits against opioid manufacturers and distributors.

To pursue his opioid lawsuits, Hunter hired private legal counsel, including Mike Burrage, the longtime general counsel for the Choctaw Nation. In February, Burrage filed an amici brief in the McGirt case in support of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s position on behalf of:

- the Choctaw Nation

- the Chickasaw Nation

- U.S. Rep. Tom Cole

- former Gov. Brad Henry

- former U.S. Rep. Dan Boren

- former Attorney General Mike Turpen

- former Oklahoma Senate Pro Temp Glenn Coffee

- former Oklahoma House Speaker T.W. Shannon

- former Oklahoma House Speaker Kris Steele

- former Oklahoma House Rep. Neal McCaleb

- former Oklahoma House Rep. Lisa Billy

- former Oklahoma House Rep. Danny Hilliard

Burrage and Robert Henry, both former federal judges, argued in the brief that the Supreme Court should “to protect the on-the-ground success of state-tribal relations in Oklahoma” by ruling against Hunter’s team in the McGirt case.

“In one area after another — taxation, gaming, motor vehicle registration, law enforcement and water rights — the nations’ sovereignty within their reservations and the state’s recognition of that sovereignty have provided the framework for the negotiation of inter-governmental agreements that benefit all Oklahomans,” Burrage and Henry argued.

Asked Monday if employing Burrage to represent his office in the opioid lawsuits while Burrage was arguing against his office in the McGirt case posed any ethical challenges, Hunter said the issues and cases were “completely separate.”

“[Mike Burrage’s] representation of the Choctaw certainly predated his involvement in the opioid litigation,” Hunter said. “He is one of the best Indian lawyers in the state. He was on the other side of the water settlement negotiations. I think everybody would agree that the outcome of the dispute with the Choctaw and Chickasaw over the waters in the southeast part of the state is something that benefits the state — certainly central Oklahoma — for decades. So his involvement in all of this is as a voice of reason — somebody who understands the issues and is focused on getting the outcome that is in the best interest of his client, in this case the Choctaw as well as the state.”

Burrage, who donated a total of $8,100 to Hunter’s campaign account in 2017 and 2018, did not respond to a request for comment prior to the publication of this story. Underscoring the difficulty of negotiations between the state of Oklahoma and multiple tribes, however, not everybody considers the 2016 water settlement Hunter referenced to have had a positive outcome.

“The water settlement in that case only applied to waters in the southeast part of Oklahoma, not the whole of the Red River, and any water west of the 98th Meridian was not included. And that included the interests of the Kiowa, Apache and Comanche nations,” said Robert Tippeconnie, secretary and treasurer for the Comanche Nation. “We feel consequently we were ignored.”

Tippeconnie said the final congressional approval of that settlement (which starts on Page 170 of the 2016 Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act) left the Comanche, Kiowa and Apache nations without certainty about their water interests.

“Our interests were not included in that settlement,” Tippeconnie said.

Four years later, Oklahoma residents and tribal citizens are again waiting to see what type of agreement can be struck to balance state and tribal interests. Hunter noted that the McGirt decision “created a significant amount of confusion,” especially as it relates to those already convicted of crimes.

But the negotiations over how much Congress should adjust jurisdiction for eastern Oklahoma’s reservations might be even more complicated.

“We continue to talk to the delegation on an almost daily basis with regard to the feedback,” Hunter said. “I’ve got to be the attorney general for all 4 million people in this state, Indians and non-Indians, and I’ve got to make a judgment what is best for everybody now and into the future.”